Featured

The Value of Values in Poverty Reduction

Scientists test culturally attuned strategies to help developing nations.

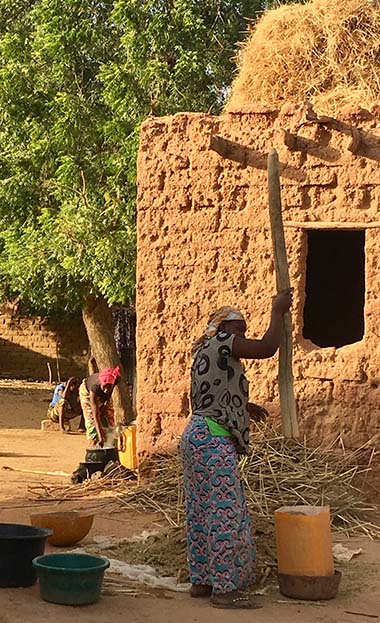

Image above: Catherine C. Thomas’s work with predominantly Muslim ethnic groups in rural Niger uses culturally tailored approaches to economic success to help lift people out of poverty. All photos in this article are courtesy of Thomas.

- Anti-poverty programs in the developing world often sputter because they clash with local culture and values.

- Many conventional interventions focus on ideals of autonomy and self-reliance that are prevalent in Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) cultural contexts, although remote, poor cultures instead value interdependence and cooperation.

- Researchers are finding success with programs that align with the tenets of the communities they’re trying to help.

- Recent studies illuminate the importance of moving beyond Western models to help people around the world transcend economic hardship.

Impact of poverty • Empowerment through education • Aligning progress with values

Food scarcity and drought pose frequent strife to communities on the edge of the Sahara Desert in rural Niger. Most women in these agrarian, predominantly Muslim groups lack education, reading ability, a cell phone, or even the opportunity to leave their villages. But schooling, technology, and mobility aren’t what they view as the core remedies for their poverty.

“When we asked women what they thought contributed to women’s economic success, they said things like peace, respecting other people, and not having tension in the household,” said Catherine C. Thomas, a psychological scientist who has tested anti-poverty initiatives in remote regions and who presented some of this research at APS’s 2023 International Convention of Psychological Science in Brussels. “If your relationship is disrupted, you have little hope of making progress for yourself.”

Most anti-poverty programs emphasize personal goals, fulfillment, and autonomy—values that clash with the interdependence that characterizes many cultures in the developing world.

But Thomas and many other social scientists are exploring the use of culturally tailored approaches to helping poor countries. These scientists are identifying some of the most cost-effective ways to lift people out of grave indigence—importantly, within the boundaries of local values.

Impact of poverty

Until recently, global poverty had been on a steady decline. Between 1990 and 2020, more than 1 billion people escaped extreme poverty, according to the World Bank. But the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have sparked economic upheavals that stalled that progress. In 2020 alone, the number of people living on as little as the equivalent of US$2.15 a day rose by more than 70 million. Today, nearly half the world—3 billion people—subsist on the equivalent of just a few U.S. dollars a day (World Bank, 2022).

Decades of studies show the psychological strain that emanates from economic peril. Eldar Shafir, a Princeton University researcher and leader in the study of poverty’s impact on behavior and decision-making, has shown that individuals forced to focus intensively on stretching their scarce resources are left with little or no mental capacity. In one study, Shafir and his colleagues tested more than 460 sugarcane farmers in India, who typically struggle financially before the annual harvest but enjoy some wealth afterward. Each farmer scored better on cognitive tests postharvest than preharvest.

In a longitudinal study, APS Fellow Gary Evans of Cornell University found that young adults who grew up in poverty showed more physiological stress, aggression, helplessness behaviors, and deficits in short-term spatial memory (Evans, 2017).

Poverty’s influence begins early in life, scientists have found. A research team led by cognitive psychologist John Spencer of the University of East Anglia used a portable neuroimaging device to study the brain function of 42 children ages 4 months to 4 years in rural India. They found that children in India from low-income families, in which mothers had low levels of education, showed weak visual working memory (Wijeakumar, 2019).

But some research focuses on the psychological assets that people living in poverty display, especially in developing countries. Drawing on data sets involving more than 3.3 million people around the globe, a team of researchers hailing from Europe, Australia, and South Korea found that low socioeconomic status is less of a burden on individuals in developing nations that tend toward high religiosity than on people living in the more secular developed world. The authors suggest that religious messaging in low-income countries may counter the social stigma associated with poverty and promote spirituality over material wealth (Berkessel et al., 2021).

Such findings have inspired some researchers to call for a new way of conducting studies with people facing deprivation. In a recent article for Current Directions in Psychological Science, APS Fellow Willem E. Frankenhuis of Utrecht University and Daniel Nettle of Newcastle University argue for integrating deficit- and strengths-based models into psychological research on poverty (Frankenhuis & Nettle, 2020).

Thomas, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University and incoming assistant professor at the University of Michigan, is among the scientists examining culture as one of those strengths. Her advisor is APS William James Fellow Hazel R. Markus, a pioneer in the field of cultural psychology. Markus has used a mix of experiments and surveys to distinguish independent cultures common in the West from the interdependent values of poorer communities (Markus & Connor, 2014; Markus & Kitayama, 2010).

In a recent article, Thomas and Markus noted that development initiatives tend to reflect Western, middle-class priorities and consequently can yield unintended results when applied to populations in, say, Africa or South Asia. Villagers in Malawi, for example, refused a nonprofit organization’s financial aid because they mistakenly believed the cash would be unfairly given only to selected households rather than to the whole community. In Sudan, individuals who had received donated food rations routed them to a village chief to allocate across the community, which led many to starve to death (Thomas & Marcus, 2022).

A team of economists found a troubling result when they tested different types of financial aid programs for women living in impoverished villages in Northern Nigeria. Women in some communities received simple monetary assistance. A year later, reports of sexual intimate-partner violence rose by 6%, the researchers found. In communities that received a more comprehensive aid package directed at everyone, not just the women, intimate partner violence dropped by 13 percentage points. The results suggested that simply directing money toward women challenged traditional norms of masculinity in those communities (Cullen et al., 2020).

Studies also show that developmental aid can negatively affect social cohesion and democratic processes, said cross-cultural psychologist Symen A. Brouwers of North-West University in South Africa.

“Recipients of aid are not a uniform group of poor people from the Third World,” Brouwers wrote in a 2018 article. “One way in which aid can move forward is by putting the cultural agendas of recipients central.”

Empowerment through education

Scientists have also examined education as a primary tool for nurturing economic security. With his colleagues, APS Fellow Michael Frese of Leuphana University Lüneburg has worked in developing countries such as Jamaica and Uganda to help people transcend poverty through entrepreneurship training (Frese et al., 2016).

Many of those educational efforts are focused on girls and women. For example, researchers in Europe conducted a field study in rural Malawi on motivating girls to stay in school. The landlocked country in southeastern Africa ranks 169 out of 188 on the United Nations’ 2016 Human Development Index. The research team aimed to test whether findings obtained in more affluent and individualistic settings would hold among people living in different life circumstances.

Psychological scientist Marieke van Egmond (Tilburg University) worked with international development organizations, including a nonprofit focused on empowering marginalized girls through school-based programs. The study involved 642 Malawian girls and young women between the ages of 10 and 22. Specially trained bilingual (English and the local language, Chichewa) interviewers surveyed the girls about their attitudes toward learning and school, their health, their income, and the difficulties they faced obtaining adequate food, medical care, and clean water.

The researchers measured each girl’s school attendance over the month of February 2015.

They found that girls most likely to attend school scored high on intrinsic motivation—that is, the girls said they enjoyed school and learning for its own sake. This held regardless of any resource scarcity that the girls experienced. Extrinsic motivation—going to school because of social expectations—had no effect on school attendance (van Egmond et al., 2017).

Such insights could ultimately lead to far-reaching benefits, van Egmond and her colleagues said. Research suggests that school attendance yields lifelong health and economic advantages for women and girls, including higher incomes, better health care, and better education for subsequent generations.

Aligning progress with values

Thomas’s work with predominantly Muslim ethnic groups in Niger reflects a science that integrates social and cultural psychology with behavioral economics. She is part of a multidisciplinary team working with collaborating organizations, including the World Bank. The research involved a sample of 4,700 households that had received money from a government cash-transfer program. The researchers assigned each household to one of four groups. Three of the groups randomly received, in addition to the monthly cash transfers, either a separate bundle of economic support that included cash grants and some business training, a psychosocial intervention, or both the economic package and the intervention.

The psychosocial component was designed to cast women’s entrepreneurship as aligned, rather than in conflict, with local cultural values. Men and women watched a short film about Amina, a woman who lifts her family and village out of financial hardship by making and selling an herb drink in the local market and creating a savings plan for her family. The intervention also involved training the women on goal setting, leadership, problem solving, decision-making, communication, and saving money.

The researchers then measured villagers’ well-being and economic conditions both 6 and 18 months after delivering the interventions. They logged improvements across various measures of psychological and social well-being, particularly among the people who received either the psychosocial or full package. In addition, the women showed more community engagement and control over their own economic activities, although their influence on decisions within the household didn’t increase.

The team also conducted a cost–benefit analysis and found the psychosocial package to be particularly effective based on the investment. (That package cost US$102 per beneficiary compared to US$584 for the full package.) The cost–benefit ratio after 18 months was 126% for the psychosocial arm, 95% for the full arm, and 58% for the capital arm.

In a follow-up, preregistered study, Thomas and her colleagues parsed out the psychosocial intervention that produced the best economic impact. They selected a subsample from the main trial involving 2,628 of the women living in the villages that received the psychosocial programs. Some were assigned to one of two more-granular psychological interventions and the rest to a control group.

In one intervention, women watched a video that depicted Amina as proactive, innovative, self-driven, and determined to be a standout entrepreneur—qualities associated with Western ideals of success. The women were then guided through an exercise in which they identified effective entrepreneurial strategies. They visualized and set personal goals. And they problem-solved on obstacles to those goals. A separate, interdependence intervention was designed to be more culturally matched: Amina was seen as more cooperative, collaborative with other women and her husband, and driven to advance her family’s well-being and become a respected community member. The guided exercise then focused on identifying effective social strategies, setting collective goals, and problem solving (e.g., resolving conflicts with family).

A year later the researchers calculated a composite score of economic security, including food security and business performance. The results, not yet published as of May 2023, showed that households receiving the interdependent intervention achieved significant gains in economic security compared to the control condition, while those receiving the independent intervention did not.

These various psychosocial interventions are now being tested in other West African nations, Thomas said. And she aims to look at culturally appropriate interventions with lower-income populations in the Philippines and India.

The studies illuminate the importance of moving beyond Western ideals of autonomy and self-reliance to help people around the world transcend economic hardship. Psychological scientists Sara Estrada-Villalta (Prescott College) and Glenn Adams (University of Kansas) have called for “decolonizing” the psychological models used to promote poverty reduction. They’ve written about the need to “challenge the global imposition of individualistic models” that ignore cultural interdependence (Estrada-Villalta & Adams, 2018).

Thomas’s experience underscores that ideal.

“Aid is not just like an economic transaction,” she said. “It’s also a cultural and social interaction. We can be part of the solution, where we’re helping populations see their own values reflected.”

Feedback on this article? Email [email protected] or login to comment. Interested in writing for us? Read our contributor guidelines.

Berkessel, J. B., Gebauer, J. E., Joshanloo, M., Bleidorn, W., Rentfrow, P. J., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2021). National religiosity eases the psychological burden of poverty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(39), Article e2103913118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2103913118

Bossuroy, T., Goldstein, M., Karimou, B., Karlan, D., Kazianga, H., Pariente, P. P., Thomas, C. C., Udry, C., Vaillant, J., & Wright, K. A. (2022). Tackling psychosocial and capital constraints to alleviate poverty. Nature, 605, 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04647-8

Brouwers, S. A. (2018). The positive role of culture: What cross-cultural psychology has to offer to developmental aid effectiveness research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(4), 519–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117723530

Cullen, C., Martinez, P. L., & Papineni, S. (2020). Empowering women without backlash? Experimental evidence on the impacts of a cash transfer and community livelihoods program on intimate partner violence in Northern Nigeria. https://custom.cvent.com/4E741122FD8B4A1B97E483EC8BB51CC4/files/csaecullengonzalezpapineniipvpaper01312020.pdf

Estrada-Villalta, S., & Adams, G. (2018). Decolonizing development: A decolonial approach to the psychology of economic inequality. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(2),198–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000157

Evans, G. W. (2016). Childhood poverty and adult psychological well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(52), 14949-14952.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1604756114

Frankenhuis, W. E., & Nettle, D. (2020). The strengths of people in poverty. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(1), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419881154

Frese, M., Gielnik, M. M., & Mensmann, M. (2016). Psychological training for entrepreneurs to take action contributing to poverty reduction in developing countries. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(3), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416636957

Markus, H. R., & Conner, A. (2014). Clash! How to thrive in a multicultural world. Penguin.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2010). Culture and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 420–430. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1745691610375557

Mani, A., Mullainathan, S., Shafir, E., & Zhao, J. (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science, 341, 976–980. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238041

Oishi, S., & Schimmack, U. (2010). Culture and well-being: A new inquiry into the psychological wealth of nations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610375561

Thomas, C. C., Markus, H. R. (2023). Enculturating the science of international development: Beyond the WEIRD independent paradigm. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 54(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220221221128

van Egmond, M. C., Navarrete Berges, A., Omarshah, T., & Benton, J. (2017). The role of intrinsic motivation and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs under conditions of severe resource scarcity. Psychological Science, 28(6), 822–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617698138

Wijeakumar, S., Kumar, A., Delgado Reyes, L. M., Tiwari, M., Spencer, J. P. (2019). Early adversity in rural India impacts the brain networks underlying visual working memory. Developmental Science, 22, Article e12822. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12822

World Bank (2022). Poverty and shared prosperity 2022: Correcting course. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1893-6

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.