Scaling Up Savings: More Targeted Policies Could Help the Hardest Hit

From health crises and job losses stemming from COVID-19 to burst pipes and other damages wrought by weather calamities, the last year has unleashed a torrent of unexpected financial emergencies upon consumers, millions of whom were already struggling to get by. Although Americans as a whole have managed to save more money than ever during the pandemic, nearly 40 percent have such a small personal safety net that they would struggle to cover a $400 emergency expense, according to a 2019 report from the Federal Reserve.

And this is despite decades of government policies and workplace programs that encourage consumers to save.

Perhaps it’s time for more targeted, science-driven approaches.

“Many policies and programs must by necessity take a generalized approach at how to change savings behavior,” wrote psychological scientist Crystal C. Hall, of the Evans School of Public Policy & Governance at the University of Washington, in a recent article in Current Directions in Psychological Science. “The tools of social and personality psychology could allow for a more nuanced and effective approach—going beyond a one-size-fits-all toolkit of interventions.”

In the article, Hall focused specifically on interventions aimed at encouraging individuals and households to save for financial emergencies. “The question of how and why individuals save is not novel,” she wrote. “The psychological sciences can go beyond simply trying to illuminate what factors are related to savings and incorporate more research on how to more effectively design interventions and mechanisms to encourage that behavior,” explained Hall, who has also applied psychological science to government policies in the federal Office of Evaluation Sciences. “More focus ought to be given to different types of individuals and population subgroups.”

Three strategies for large-scale interventions

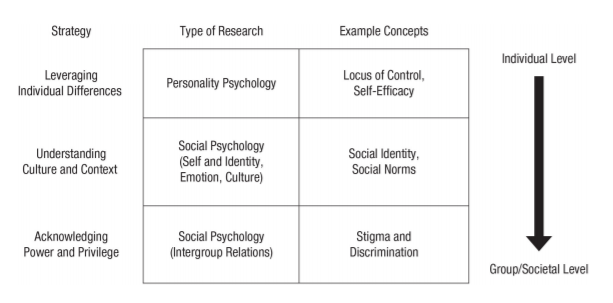

In her analysis, Hall reviewed prior attempts to use psychological insights to increase the rate at which consumers save, with varying degrees of success. She also highlighted three science-based strategies for capitalizing on these and other insights on a larger scale going forward: leveraging individual differences, understanding culture and context, and acknowledging systems of power and privilege.

In prior work, a common approach has promoted savings interventions during tax season, given that tax refunds provide a unique yearly windfall to many low- to moderate-income tax filers and thus represent a savings “reset point.” $aveNYC, for example, was a matched-savings program offered to low-income tax filers at volunteer income-tax assistance sites in New York City. Designed to avoid the use of formal (and sometimes expensive) features such as financial education, its low-touch approach increased participants’ likelihood of setting aside a month of living expenses, according to a 2015 study cited by Hall.

Another approach is prize-linked savings (PLS) accounts, which reward account holders using a lottery-like drawing in which the chance of winning is proportional to the account balance. The goal “is to capitalize on the appeal of gambling to incentivize people to invest in their personal savings account,” Hall wrote. “Although these programs are far from ubiquitous in the United States, they hold promise as a creative means to increase savings behavior. They are clearly rooted in strong insights regarding the psychology of savings and gambling, and their design and implementation could be further enhanced by more deeply incorporating features informed by social and personality psychology.”

In outlining strategies for designing scalable savings interventions going forward, Hall called first for “a deeper exploration of individual differences as they relate to savings.” Personality traits such as strong locus of control (the degree to which people believe they have control over life outcomes) and higher self-efficacy, for instance, have been associated with greater wealth accumulation. Gender and variables such as materialism and view of the self in the future also relate to saving and spending behaviors. “Systematic and expanded work in these areas may provide evidence to inform more nuanced approaches to encouraging individual saving across a diverse set of people and social contexts.”

Second, Hall noted, “social psychology provides many tools to help understand (or create) the social environment that promotes or prevents savings behavior.” Consider identity priming, which shows that individual behavior is often consistent with the aspect of one’s identity that is salient at the time of a choice. Tools such as parental identity, along with simple visual reminders of financial goals (e.g., photos of children or grandchildren), could be leveraged to encourage consumers to practice self-control when it comes to building a modest rainy-day fund.

“The final, and perhaps most important, strategy is understanding and addressing how structures and forces of power create institutions that perpetuate financial disparities and then using that understanding to rebuild these institutions,” Hall wrote. “For example, research on the psychology of intergroup relations can be applied to understand how forces such as stigma, prejudice, and discrimination manifest in the financial institutions and practices that promote or prevent long-term financial stability.” Self-affirmation interventions, for example, have been shown to attenuate the stigma of poverty for low-income decision-makers, she noted.

“The bottom line is relatively straightforward,” Hall wrote. “Simple, blanket nudges tend to create only modest impacts in both the propensity to save and the amount saved…. Psychologically informed approaches have the potential to improve equity by more comprehensively focusing on the diverse array of social contexts in which individuals have the ability and intention to save.”

Reference

Hall, C. C. (2021). Promoting savings for financial resilience: Expanding the psychological perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(1):49–54. https:/doi.org/10.1177/0963721420979603