Featured

Women in Psychology: An Uneven Playing Field

Women are more represented in psychological science than ever, but obstacles remain. COVID-19 “is just breaking the back of an already strained system.”

For an abbreviated progression of women’s representation in psychological science over the last century, consider the experiences of Lillian Moller Gilbreth and Tessa Charlesworth.

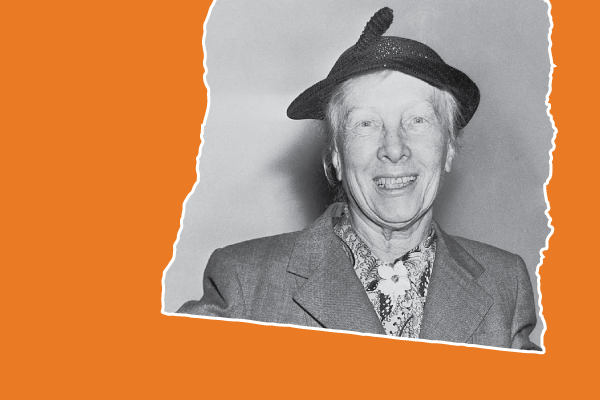

Pioneering psychological scientist Gilbreth, pictured above, coauthored several books with her husband and business partner, Frank, until his death in 1924. The couple had 12 children, so it’s possible that between raising them and pursuing her career as an industrial psychologist, inventor, college professor, filmmaker, and author of her own books, she didn’t have time to get particularly rankled by the omission of her name from the coauthored books’ credits.

“Publishers believed that including a woman as an author would hurt the books’ credibility. At the time, Gilbreth was among the few practicing industrial psychologists with a doctorate; her husband hadn’t been to college” (Observer, 2017).

More than 90 years later, Charlesworth was in her first year of graduate school at Harvard when, at a meeting at another university, “a male colleague turned to me, the only woman in the room, and essentially said, ‘You’re only here because I invited you.’”

(Harvard University) Photo by Stu Rosner

“I was shocked,” said Charlesworth, now a doctoral student studying attitude and stereotype change, implicit social cognition, and quantitative methods. “These were people who researched attitudes and social biases.” Despite that, in the years since, she has heard explicit expressions of gender bias from researchers in the field.

“They might say to a female scientist, ‘We’re going to add you as an author because we need more female representation in the authorship,’ or ‘We need a female on the panel,’ rather than, ‘We love your work, and we want you to contribute,’” Charlesworth explained.

Is this how progress is supposed to work?

Charlesworth shared these experiences in mid-November 2020—near the end of a year whose few positive developments included the elevation of a number of prominent women in fields once dominated by men. Kamala Harris was elected the first female vice president of the United States. New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern, Germany’s Angela Merkel, and Taiwan’s Tsai Ing-wen were among a handful of global leaders to win praise for their handling of the COVID-19 crisis (Goswami, 2020). Record numbers of female CEOs were at the helm at Fortune 500 companies (Fuhrmans, 2020). Even fall’s breakout Netflix hit, The Queen’s Gambit, featured a woman (albeit a fictional one) celebrated for her genius in the male-dominated world of chess.

Gender Disparities in Academia Worldwide

- AUSTRALIA: Women held 54.7% of lecturer positions, 46.8% of senior lecturer positions, and just 33.9% of positions above senior lecturer (2018).

- CANADA: Women made up 55% of positions below assistant professors but only 28% of professors (2018–2019).

- EUROPEAN UNION: Women accounted for 41.3% of all academic positions but just 23.7% of senior academic positions (2016).

- INDIA: Women held 42.6% of lecturer and assistant professor positions, 36.8% of reader and associate professor positions, and only 27.3% of professor and equivalent faculty positions (2018–2019).

- JAPAN: Women represented 52.3% of full-time junior college teachers but just 24.8% of full-time university teachers (2018).

- UNITED STATES: Women accounted for 57% of instructors, 52.9% of assistant professors, 46.4% of associate professors, and just 34.3% of full professors (2018).

Source: Catalyst (2020).

Women hit new highs within the field of psychological science, too.

“Women make up a large and growing proportion of today’s psychological scientists,” wrote APS Fellow June Gruber (University of Colorado, Boulder), Jane Mendle (Cornell University), Kristen A. Lindquist (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), and 56 other women in “The Future of Women in Psychological Science,” a 2020 report in Perspectives on Psychological Science. Women represent 78% of undergraduates and 71% of graduate students in psychology, they noted. In addition, women are “increasingly visible in leadership positions: They head prominent laboratories, departments, and professional societies; play key roles in navigating the direction of psychological science; and are mentoring the next generation of scientists.”

But Gruber and colleagues also noted persistent gender gaps, which are heightened for people of color, people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT), and people with disabilities. For instance, female associate professors make 92% as much as male associate professors; among full professors, that share falls to 88%. In addition, “women in psychological science who secure tenure-track positions publish less, are cited less, hold fewer grants, [and] are less likely to be represented in the field’s most eminent roles,” Gruber and colleagues wrote. They also cited data suggesting that women remain underrepresented at the more senior levels of their fields, including the rank of full professor.

“One interpretation of this reduction in more senior women scholars is that there is a ‘leaky pipeline’. . . whereby women leave the field at higher rates than men as they progress to more senior phases of their careers,” Gruber and colleagues wrote. “A second interpretation is that the narrowing of gender differences in early-career phases has not yet had time for those women to reach more senior career phases… A third interpretation is that there are gender differences in factors that relate to career advancement.”

In an episode of APS’s Under the Cortex podcast featuring several “Future of Women” authors, Gruber recalled her own “sobering experiences during my maternity leave and some of the treatment I received from my colleagues at the time. I think many of us had assumed in some ways that psychological science was a model of gender parity, having had incredible female role models during many of our own trainings. Yet these lived experiences that we began to discuss and share among women colleagues revealed what seemed to be really glaring issues and impediments that women were still facing in our own field.”

In September 2020, APS published the first-ever gender parity review of psychological science: “The Future of Women in Psychological Science.” The story behind this study, as told by some of the authors, is a compelling examination of personal experiences and observations.

Bearing the brunt

Gruber and colleagues also found that psychology professors and instructors who are women are more likely to perform lower-status services within their departments and broader scholarly communities, such as committee work and supervision, along with other services like informal mentorship. A clear factor in that discrepancy is the department chair’s gender: Within the social sciences, women’s service more than doubles when their department chair is male.

“The expectation that women are nurturing caregivers who gladly do unpaid tasks in their departments as well as at home—these societal norms clearly trickle down to women’s own beliefs about themselves.”

Kristen A. Lindquist (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

“The expectation that women are nurturing caregivers who gladly do unpaid tasks in their departments as well as at home—these societal norms clearly trickle down to women’s own beliefs about themselves,” observed Lindquist in the podcast.

As to why women submit fewer papers and receive fewer grants, Lindquist suggested it might be “because their time is spent elsewhere”—that is, performing services—“or because they’re either more perfectionistic about those products or they believe that they’re less deserving of them, or they’re less likely to receive them if they apply.”

(Texas A&M University)

This service load appears to be especially heavy for women of color, who “may be expected to engage in additional service relating to diversity,” Gruber and coauthors wrote. One coauthor, Adrienne Carter-Sowell (Texas A&M University), noted the exacerbating influence of intersecting inequalities during the podcast. “Despite the compounded burdens that are faced by many women scholars of color, the research shows that there’s really little attention to the successes gained or the personal financial health and well-being costs paid by women scholars of color who are persisting and existing in the field,” she said.

Women—especially Black women, who are more likely to be their family’s primary earner and caregiver—have also borne the brunt of job losses due to COVID-19.

Between November 2019 and November 2020, the overall unemployment rate for women in the United States more than doubled, from 3.3% to 6.4%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics; some 956,000 women left the workforce in September alone. Over the summer, almost one in three women (32.1%) ages 25 to 44 had left their jobs because of childcare demands, compared to 12.1% of men, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau and Federal Reserve. But the unemployment rate for Black women is 9.3%, according to Janelle Jones of the Groundwork Collaborative. “That is a crisis,” especially on top of the existing economic disparities facing Black women, Jones said in an episode of NPR’s Marketplace in November. “White women have recovered 61% of the jobs they lost since the recession [began]. Black women have only recovered 34%.”

Within academia specifically, an enormous study of scientific publishing provided evidence that “female academics are taking extended lockdowns on the chin, in terms of their comparative scholarly productivity,” according to an analysis in Inside Higher Education (Flaherty, 2020). The study, based on submitted manuscripts and peer-review activities at Elsevier journals between February 2018 and May 2020, found that female academics across all levels of seniority in the social sciences and economics accepted far fewer peer-review invitations between February and May of 2020 than in the same period in 2019.

“Unfortunately, COVID mimics a life that many of us have been living long before February of 2020… This is just breaking the back of an already strained system.”

Adrienne Carter-Sowell (Texas A&M University)

“Unfortunately, COVID mimics a life that many of us have been living long before February of 2020,” Carter-Sowell told the Observer in November. “You’re isolated, overworked, juggling more than ever before, dealing with family falling apart for reasons that you can’t control. This is just breaking the back of an already strained system.”

Carter-Sowell speaks from experience. She now serves as the associate head of diversity, equity, and inclusion as well as an associate professor of both psychological and brain sciences and in the interdisciplinary critical studies program at Texas A&M. She is an authority on topics including ostracism and its effects on the psychological, cognitive, and behavioral responses of individuals and groups.

Within her research lab, Carter-Sowell mentors nine people (undergraduate and graduate students, a postdoctoral researcher, and a visiting scholar). She’s also a parent and her family’s main breadwinner. And like many, she doesn’t have “the resources that allow you to write your amazing top-tier-journal papers over the summer because you have to cover expenses 12 months of the year,” she said.

“Have I made it? Did we make it? I mean, I’m excited I got the degrees,” Carter-Sowell said. “But academia never lets you know if you’ve made it.”

That chilly feeling

For all their gains, women are confronted by subtle—and not-so-subtle—reminders of gender disparity in the halls of academia every day.

“A lot of them are really simple—like, does your department have a wall full of every former department chair, and they’re all men?” asked Elizabeth Cole, a professor of women’s studies and psychology at the University of Michigan. “My friends and I call that the ‘stereotype threat wall.’”

(University of Michigan)

She cautioned that in many ways, both explicit and implicit, “how we do the business of the academy serves to send messages about who’s in and out.” These signals might seem innocuous to some people, but “other people might say, ‘this isn’t for me.’”

Extensive research has explored why gender gaps exist in psychological science, from systemic factors (including socialized gendered roles and work-family conflicts) to cultural stereotypes and outright gender bias. These factors start taking root early in life.

In a recent exploration of gender stereotypes in natural language in press at Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Charlesworth, her advisor, APS Past President Mahzarin Banaji (Harvard University), and coauthors point to “the natural language of human conversations, books, and audiovisual media for both children and adults” as gauges for measuring the implicit presence and potency of group stereotypes. “Take, for example, innocuous child-directed statements such as ‘get Mommy from the kitchen’ or ‘Daddy is still at the office,’” they write. “Such sentences do more than describe the physical locations or roles of mothers and fathers; they also reinforce attributes associated with those roles.”

“How we do the business of the academy serves to send messages about who’s in and out.”

Elizabeth Cole (University of Michigan)

When she was a child, Charlesworth herself heard few such expressions. Growing up in British Columbia, Canada, “I came from this line of go-getter women,” she said, including “a single mom who was just ready to take on the world. She really believed that I could do anything.” Charlesworth’s grandmother was among the first licensed female architects in British Columbia, and Charlesworth too hoped to be an architect, bolstered by her love for math and classes like calculus and physics.

Her curiosity about psychology and gender bias wasn’t piqued until she took an intro psych class at the all-women’s Barnard College while she was an undergraduate at Columbia University.

“It was absolutely amazing,” she said. “I was surrounded by 100 other women, and the idea of being able to quantitatively and experimentally manipulate behavior or to quantify social structures just blew my mind.”

Then, in a summer internship at the University of British Columbia under the supervision of Andrew Baron and Antonya Gonzalez, she assisted on a study of stereotype threat. Girls 5 and 6 years old were given a simple counting task and were told that it was either a test or a game. When asked about how much they liked math, the girls discounted their skills, “saying things like, ‘Oh, I used to really like counting things on the refrigerator, but now I think I’m better at writing,’” Charlesworth remembered. “You could almost see, even at that age, a kind of tension in their minds.”

Shortly thereafter, she read a paper showing that young children’s in-group preferences (e.g., girls prefer the company of girls; Black children prefer the company of Black children) go away as they get older. In line with the broader culture, kids “start to prefer the dominant, higher-status social groups,” Charlesworth said. “It was so disheartening… I was like, ‘These kids, they’re internalizing this culture of oppression, essentially, at such early ages.’”

The gender biases that we begin to internalize in childhood often deepen in the years that follow. In a 2020 study, Charlesworth and colleagues explored a “gender-brilliance stereotype” across more than 3,000 people in more than 70 countries. The results showed that “people had an implicit association of males with brilliance and women with traits like creative, or happy, or even funny,” she said, whether the males were White or Black or whether gender was captured in words or depicted through images.

“Threats to this identity—such as an increasing number of women in a male-dominated area—can lead to in-group bias… An outcome of this bias is the ‘chilly climate’ for women in academia—the perception of an exclusionary workplace environment.”

Adrienne Carter-Sowell (Texas A&M University) and colleagues

These kinds of associations, compounded by variables that can include race and socioeconomic status, often play out in the workplace. Carter-Sowell’s research has shown how women and people of color often experience a sense of being “out of the loop” in the workplace, which can negatively affect their recruitment, retention, and promotion in scientific and technical fields. “People seek to maintain a positive and distinct social identity, in comparison to other groups,” Carter-Sowell and colleagues wrote in 2016 in Frontiers in Psychology (Zimmerman et al., 2016). “Threats to this identity—such as an increasing number of women in a male-dominated area—can lead to in-group bias… An outcome of this bias is the ‘chilly climate’ for women in academia—the perception of an exclusionary workplace environment. Indeed, women report greater exclusion from informal networks compared to male colleagues.”

Growing up in Virginia’s Tidewater region, Carter-Sowell knew what ostracism felt like long before she had a word for it. At home, she heard messages meant to protect her. “There were neighborhoods we couldn’t live in and pools we could not join and places we did not go. It wasn’t legal to say that you weren’t permitted, but you were aware of where you were excluded.” Then, in school during the 1970s and 1980s, despite a statewide desegregation process that had begun in 1959, she noticed a tracking system that steered White students into more advanced classes, often to the exclusion of equally intelligent Black students like herself.

She received far more encouragement at home, but there, expectations often divided along gender lines.

“I came from a very supportive family who valued education, but the males were often embraced for their engineering and math skills in a way that the females were not,” she said.

Even as she excelled academically, Carter-Sowell repeatedly experienced that sense of not quite belonging. She graduated from the University of Virginia (UVA), where, 2 decades earlier, her uncle had received an academic scholarship from the college of engineering but encountered a racial climate so hostile that he dropped out before getting a degree. When she arrived in 1986, she found a campus somewhat more welcoming, but her uncle’s experience had prepared her—and it prepared her family, too.

“They all rallied around me,” she said. “It was just this whole, huge family effort that they were going to invest in my getting through UVA. They had no idea what graduate school was.”

Carter-Sowell did make it, with a degree in sociology and rhetoric/communications, but vague notions of graduate school quickly faded, thanks in part to advisers who suggested that her being a first-generation college student might somehow set her up to fail. It wasn’t until several years later, while she was working for a textbook publishing company in California, that the author of an introductory psychology textbook noted her interest in workplace dynamics and planted the idea of getting a PhD in psychology. He helped her understand the funding process for graduate and doctoral students and wrote her a letter of recommendation for Purdue. Once there, she began anew as a “nontraditional student” who was older than most of her classmates and, again and again, “the only Black person and female graduate student in the lab in the lab.”

Looking back, “I think I could articulate chilly climate before there was a chilly climate concept,” Carter-Sowell said.

Related content from this issue:

- From Words to Action: Higher education shifts gears in taking on diversity, equity, and inclusion

- Turning the Page: Academic publishers confront a stubborn absence of diversity

- The Bias of Crowds: How social environments change our minds

- Up-and-Coming Voices: Previews of emerging research on inclusivity

The ways forward

Mentorship: The speed pass of academia

When Elizabeth Cole started graduate school in clinical psychology at the University of Michigan, she nearly dropped out, deeply dissatisfied by what at the time was a psychoanalytical approach that “saw people in such individualistic terms,” she said. “It didn’t seem to have any mechanism to think about inequality and how that shapes people’s lives.”

One day on the street, she happened to run into Abigail Stewart, her former undergraduate adviser at Boston University, who had also moved to Michigan. Stewart talked Cole into staying and switching to personality psychology, and to this day the two tenured professors remain close.

“I really think my whole career has been possible because of the mentors I’ve had,” Cole said.

Women mentors, from her barrier-breaking mother and grandmother to her later peers and advisors, including Banaji, have also been crucial to Charlesworth’s career.

“I’ve seen these women and recognized, ‘Oh, look, there is actually another woman doing quantitative work,’ rather than just saying ‘Well, no one like me has ever done it before—so why would I think I could do it?’”

Tessa Charlesworth (Harvard University)

“That’s been the case throughout my entire trajectory. I’ve seen these women and recognized, ‘Oh, look, there is actually another woman doing quantitative work,” Charlesworth said, “rather than just saying, ‘Well, no one like me has ever done it before—so why would I think I could do it?’”

For Carter-Sowell, a pivotal mentoring experience occurred when she came to Texas A&M as an assistant professor in 2010. Under a program aimed at diversifying faculty at the university, she and other newly hired women of color had the opportunity to be assigned not just one mentor, but two. One of Carter-Sowell’s mentors was an external scholar, who was in her field but outside Texas A&M; this person gave her a bird’s-eye view of the field at large.

The second was an internal scholar from outside the field and inside the university, who “told me everything I needed to know to be successful at Texas A&M,” she said. That dual-mentorship program “is why I’m here today. It was like going to Disney World with the speed-pass bracelet; you’re getting reliable experts to guide you through your early career.”

Building a better profession

Among other practices that can pave a way forward for women in psychological science, Charlesworth and Carter-Sowell proposed two that stand out.

At the individual and department levels, Charlesworth advises taking “a really critical perspective on what we’re doing every day. Think of this as a self-auditing activity,” in terms of the language you use and the behaviors and assumptions you’re making. “Then ratchet that up at the departmental level.” For instance, does your department have its own version of the “stereotype threat wall”?

“It’s really only in understanding the beast that we’re tackling that we can actually tackle it.”

Adrienne Carter-Sowell (Texas A&M University) and colleagues

At the structural or societal level, ask critical questions akin to those raised by the Black Lives Matter and Me Too movements. “Really think about it. What are the ways that gender-based privilege and race-based privilege play out in our society? It’s really only in understanding the beast that we’re tackling that we can actually tackle it,” Charlesworth said.

For her part, Carter-Sowell calls for more unfiltered honesty about the challenges women and marginalized members of the field can expect to confront. Some may lack the advantages many of their peers have, from inside knowledge about institutional processes, to reassurance in being seen and asking for exactly what they want without consequences or added workload, to community support for partners and children not affiliated with the university.

“It’s the assumption that we’re all operating on a level playing field,” Carter-Sowell said. “And it’s just not true.”

She elaborated on these concerns in the “Future of Women” episode of Under the Cortex. The more women in the field share the challenges they’ve faced, the better off “we all ares… for bringing light to areas that were not part of the conversation and making all of us accountable for being a better profession than we were,” Carter-Sowell said.

Feedback on this article? Email [email protected] or scroll down to comment.

References

Association for Psychological Science. (2020, November 12). The story behind the “Future of Women in Psychological Science” [Audio podcast episode]. In Under the Cortex.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). The employment situation—November 2020 [News release]. U.S. Department of Labor.

Catalyst. (2020, January 23). Women in academia: Quick take.

Storage, D., Charlesworth, T. E. S., Banaji, M. R., & Cimpian, A. (in press). Adults and children implicitly associate brilliance with men more than women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Flaherty, C. (2020, October 20). Women are falling behind. Inside Higher Education.

Fuhrmans, V. (2020, November 5). There are more female CEOs than ever, and many of them are in retail. The Wall Street Journal.

Goswami, N. (2020, November 19). Have female CEOs coped better with Covid than men? BBC News.

Gruber, J., Mendle, J., Lindquist, K. A., Schmader, T., Clark, L. A., Bliss-Moreau, E., Akinola, M., Atlas, L., Barch, D. M., Barrett, L. F., Borelli, J. L., Brannon, T. N., Bunge, S. A., Campos, B., Cantlon, J., Carter, R., Carter-Sowell, A. R., Chen, S., Craske, M. G., . . . Williams, L. A. The future of women in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620952789

Heggeness, M. L., & Fields, J. M. (2020, August 18). Working moms bear brunt of home schooling while working during COVID-19. U.S. Census Bureau.

Ryssdal, K. (Host). (2020, November 23). The economic EGOT? [Audio podcast episode]. In Marketplace. NPR.

Observer. (2017, September 19). ‘A genius in the art of living’: Industrial psychology pioneer Lillian Gilbreth.

Squazzoni, F., Bravo, G., Grimaldo, F., Garcıa-Costa, D., Farjam, M., & Mehmani, B. (2020). No tickets for women in the COVID-19 race? A study on manuscript submissions and reviews in 2347 Elsevier journals during the pandemic. SSRN. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3712813

Zimmerman, C. A., Carter-Sowell, A. R., & Xu, X. (2016). Examining workplace ostracism experiences in academia: Understanding how differences in the faculty ranks influence inclusive climates on campus. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 753. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00753

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.