Practice

Teaching: Big Smile—Distant Diversity Drives Emotion Culture

Aimed at integrating cutting-edge psychological science into the classroom, Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science offers advice and how-to guidance about teaching a particular area of research or topic in psychological science that has been the focus of an article in the APS journal Current Directions in Psychological Science.

Also see Teaching: Phenomenological Control—What Is Reality, Really?

Visiting a certain U.S. Midwestern state, you might hear about “Minnesota nice”—the stereotype that Minnesotans are friendly, self-deprecating, and polite. (Indeed, compared with other states, Minnesotans actually are fairly extroverted and agreeable; Rentfrow et al, 2008.) Some countries are similarly stereotyped: Perhaps you’ve heard that people from Brazil express stronger positive emotions (something that data also support; e.g., Krys et al., 2022).

According to one explanation, these cultural patterns began decades ago. Current inhabitants of Minnesota had historical ancestors who settled the state along with emigrants from all over the world. Today’s “Minnesota nice” is a cultural solution to a previous problem: the need to collaborate with neighbors from Poland, Sweden, Norway, and England. Modern residents of Brazil descended from people living in similarly diverse communities. In these regions, people had to work together with neighbors who didn’t speak their language or share their emotional norms.

In their Current Directions review, Paula Niedenthal and colleagues (2023) outline the ancestral diversity theory of culture and human emotion. Their theory is a socioecological approach to culture in which culturally different habits are seen as solutions to past challenges in the social and physical environment.

The World Migration Matrix indexes worldwide ancestral diversity (Putterman & Weil, 2010). In some world areas, people’s ancestors were from pretty much the same region. But in others, colonialization, voluntary immigration, and forced migration meant that ancestors interacted with folks from many different places. The matrix indicates that Brazil, the United States, Australia, and Canada are among the most ancestrally diverse countries, while China, Japan, Ethiopia, and Norway are among the least. Within the United States, California, New York, and—yes—Minnesota are more ancestrally diverse than Mississippi, Delaware, and Georgia.

In ancestrally diverse regions, people didn’t share a common language or emotional expression practices. Over time, across multiple interactions and collaborations, people developed new emotional expression norms. For one, people expressed their emotions more clearly: Clear facial expressions can communicate where language fails. And they began the habit of offering more affiliative and rewarding smiles, which establish trust and facilitate collaboration, respectively (Martin et al., 2017). To see examples of these smiles, watch the gifs on this website: https://www.niedenthalemotionslab.com/social-functions.

Easy-to-read faces. Multiple studies support the theory. For example, one team reanalyzed data from studies that used emotional faces from multiple cultures (Wood et al., 2016). When targets came from more ancestrally diverse countries, their facial expressions were more accurately interpreted by others: They were easier to read.

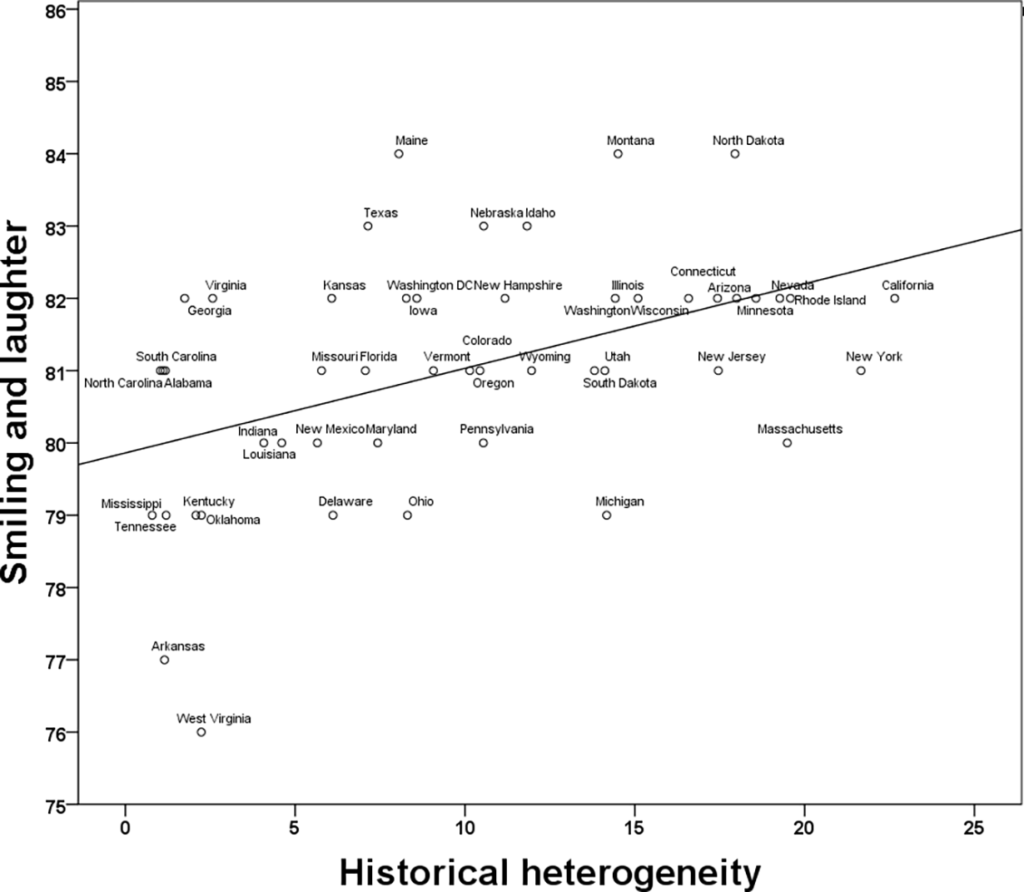

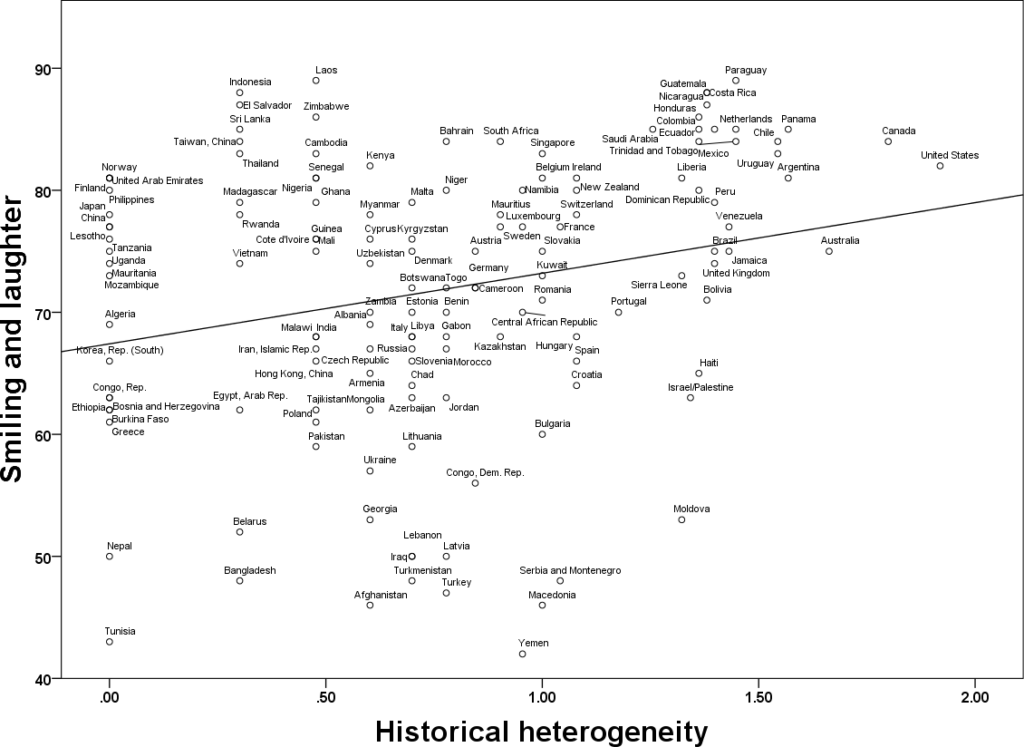

Friendly, cooperative smiling. Smiling behavior also tracks ancestral diversity. One team used data from the 142 countries in Gallup World Poll’s daily index, which asks, “Did you smile or laugh yesterday?” People from countries with more ancestral diversity were more likely to report smiling or laughing (Niedenthal et al., 2018). Within the United States, the same pattern holds: Ancestrally diverse Minnesotans smile more than ancestrally homogenous Mississippians. Importantly, these studies control for several alternative explanations, including GDP, population density, and present-day diversity.

If your students have learned about basic scatterplots, they’ll enjoy studying the results from these studies, perhaps locating their home countries or states:

When explaining these patterns, it’s important to communicate that ancestral diversity is different from present-day racial or ethnic diversity. In fact, some studies show that current diversity may drive bias, not emotion. Students may enjoy speculating about the role of city stereotypes or current economic practices such as tourism.

After introducing the theory, illustrate one of its mechanisms with this game. Sort the class into groups of three or four. Each group will have two “players” and one or two “observers.” The players will collaborate to earn virtual money by blowing up a virtual balloon—the Balloon-Analog Risk Task (BART). The observers will tally the players’ smiles and frowns as they work together.

Here’s how it works: The two players sit side by side in front of one laptop and open https://www.brainturk.com/bart. Each mouse click earns 5 virtual cents and inflates, bit by bit, a virtual balloon. At any point in a trial, the balloon could pop and any money earned on that trial vanishes. As you introduce the task, emphasize collaboration: Pairs must alternate who controls the mouse in each trial and mutually agree to keep clicking or cash in.

Here’s the twist. Tell half the pairs they come from different countries: They don’t speak the same language so they can’t talk. The other pairs share a language and are allowed to talk.

After all groups have completed the task, collect the smile and frown counts, sorted by whether the pairs were allowed to speak or not, and show the graph to the class.

In the study on which this exercise is based (Zhao et al., 2023), nontalking pairs coordinated their facial expressions and used more frowns and reward smiles. The finding illustrates a potential causal mechanism: If a region is populated with people who can’t yet talk to each other, facial expressions aid collaboration.

Feedback on this article? Email [email protected] or login to comment. Interested in writing for us? Read our contributor guidelines.

Krys, K., Vignoles, V. L., de Almeida, I., & Uchida, Y. (2022). Outside the “cultural binary”: Understanding why Latin American collectivist societies foster independent selves. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(4), 1166–1187. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916211029632

Martin, J., Rychlowska, M., Wood, A., & Niedenthal, P. (2017). Smiles as multipurpose social signals. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(11), 864–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.08.007

Niedenthal, P. M., Rychlowska, M., Wood, A., & Zhao, F. (2018). Heterogeneity of long-history migration predicts smiling, laughter and positive emotion across the globe and within the United States. PLOS ONE, 13(8), Article e0197651. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197651

Putterman, L., & Weil, D. N. (2010). Post-1500 population flows and the long-run determinants of economic growth and inequality. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(4), 1627–1682. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2010.125.4.1627

Rentfrow, P. J., Gosling, S. D., Potter, J. (2008). A theory of the emergence, persistence, and expression of geographic variation in psychological characteristics. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 339–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00084.x.

Wood, A., Rychlowska, M., & Niedenthal, P. M. (2016). Heterogeneity of long-history migration predicts emotion recognition accuracy. Emotion, 16(4), 413–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000137

Zhao, F., Wood, A., Mutlu, B., & Niedenthal, P. (2023). Faces synchronize when communication through spoken language is prevented. Emotion, 23(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000799

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.