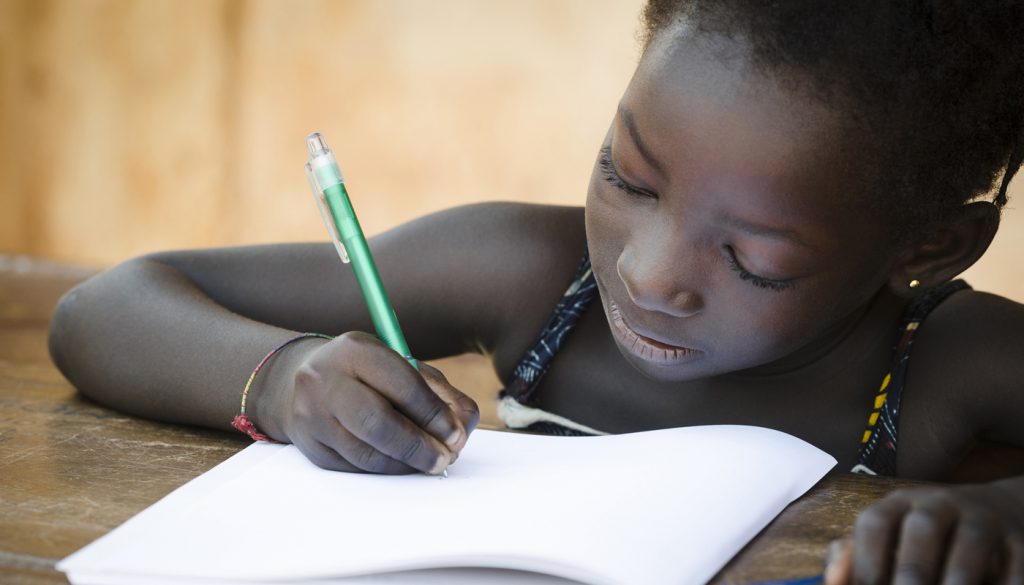

Fostering Motivation Could Help Keep Marginalized Girls in School

Education — and girls’ education in particular — is often cited as one of the key pathways out of poverty, but in many parts of the world women and girls still face significant barriers that prevent them from attending school. Now, a field study in Malawi reveals psychological factors played an important role in whether girls attended school, even under conditions of extreme poverty and deprivation: Girls were significantly more likely to attend class when they were intrinsically excited about school and learning, even when they struggled with a lack of basic resources at home.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

“We are prone to think that giving girls a reward for going to school will increase their motivation. Instead, our results indicate that stimulating their intrinsic joy of learning is a stronger predictor of their actual school going behavior, even under conditions of severe poverty,” says researcher Marieke van Egmond of the University of Hagen in Germany, lead author on the study.

Even though a significant part of the global population lives under conditions of poverty, empirical psychological research with people living in poverty around the world is rare. Studies like this one are vital to determining whether theories and findings obtained in Western, industrialized settings hold for people who are exposed to very different life circumstances.

“In general, girls really want to go to school, enjoy learning, and go to great lengths to do so. In psychological terms, they are intrinsically motivated,” van Egmond explained. “Poverty and social dynamics, however, work against them. Cultural beliefs and attitudes reinforce the idea that girls won’t use their education or that they are not smart enough to continue with school. In other words, they don’t feel like they belong in school, they don’t feel competent and lack power.”

To better understand the psychological factors that can help marginalized girls stay in school, van Egmond teamed up with the international development non-profit Theatre for a Change (TfaC) and researchers from One South to conduct a field study. TfaC’s program focuses on empowering marginalized girls through school-based girls clubs.

Study participants included 642 girls and young women between the ages of 10 and 22 years old living in rural Malawi, a landlocked country in southeastern Africa that ranks 170 out of 188 on the United Nation’s 2016 Human Development Index. Participants were randomly selected from girls attending schools in Theatre for a Change school programs.

Interviews for the study were conducted by a specially trained team of 24 bilingual (English and Chichewa) female interviewers. The interviewers surveyed the girls about their intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for attending school, their health, and how frequently they didn’t get enough to eat, didn’t have enough clean water, lacked medicine or medical treatment, or lacked any cash income.

The researchers measured school attendance by looking at the number of days that girls had attended school over the month of February 2015.

School attendance was significantly higher among girls who were intrinsically motivated to attend school – those who said they enjoyed school and learning for its own sake – regardless of the level of resource scarcity that the girls were exposed to. Extrinsic motivation – that is, going to school because it is expected or normative — did not predict school attendance.

The results suggest that interventions that target aspects of intrinsic motivation, such as a sense of competence and autonomy, may be as effective as economic approaches in achieving behavioral change, as long as fundamental structural barriers (such as access to pens and paper) are overcome.

“The take home message is that development projects that aim to increase the school attendance of girls in impoverished settings need to not only aim for female empowerment, but for creating environments in which girls feel that they belong and feel able to learn as well,” van Egmond says. “This will stimulate the girls’ intrinsic motivation to go to school, which is a strong predictor of their actual attendance.”

Such interventions could ultimately lead to wide-ranging benefits, as research suggests that attending school provides lifelong health and economic advantages to women and girls, including higher incomes, better health care, and better education for ensuing generations. Yet, according to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, there are 33 million fewer girls than boys in primary schools worldwide.

Van Egmond and colleagues plan on extending this research to other countries in the sub-Saharan region in order to see if the patterns observed hold in different cultural contexts.

Co-authors on the research include Andrés Navarrete Berges and Tariq Omarshah of One South and Jennifer Benton of Theatre for a Change.

Theatre for a Change Malawi received funding from the U.K. Department for International Development. The current project was funded within the framework of the Girls Education Challenge (Reference No. 8329).

All materials have been made publicly available via the Open Science Framework. The complete Open Practices Disclosure for this article is available online. This article has received the badge for Open Materials.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.