Language on Twitter Tracks Rates of Coronary Heart Disease

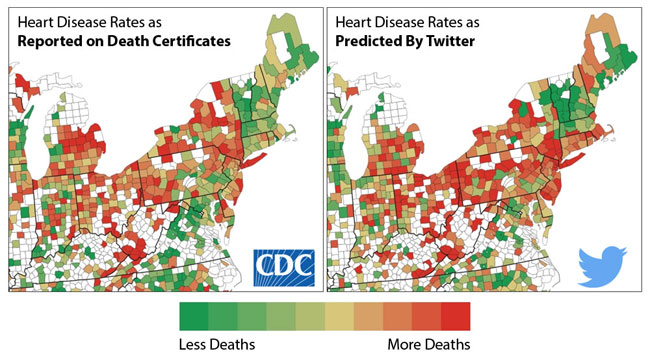

Twitter can serve as a dashboard indicator of a community’s psychological well-being and can predict county-level rates of heart disease, according to new research published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

Previous studies have identified many factors that contribute to the risk of heart disease, including behavioral factors like smoking and psychological factors like stress. Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania demonstrated that Twitter can capture more information about heart disease risk than many traditional factors combined, as it also characterizes the psychological atmosphere of a community.

The findings show that expressions of negative emotions such as anger, stress, and fatigue in the tweets from people in a given county were associated with higher heart disease risk in that county. On the other hand, expressions of positive emotions like excitement and optimism were associated with lower risk.

The results suggest that using Twitter as a window into a community’s collective mental state may provide a useful tool in epidemiology:

“Getting this data through surveys is expensive and time consuming, but, more important, you’re limited by the questions included on the survey,” said psychological scientist Johannes Eichstaedt, who led the study. “You’ll never get the psychological richness that comes with the infinite variables of what language people choose to use.”

Having seen correlations between language and emotional states in previous research, the scientists wanted to see if they could find evidence linking those emotional states to physical outcomes.

“Psychological states have long been thought to have an effect on coronary heart disease,” said co-author Margaret Kern of the University of Melbourne in Australia. “For example, hostility and depression have been linked with heart disease at the individual level through biological effects. But negative emotions can also trigger behavioral and social responses; you are also more likely to drink, eat poorly and be isolated from other people which can indirectly lead to heart disease.”

As a common cause of early mortality, public health officials carefully count when heart disease is identified as the underlying cause of death. They also collect meticulous data about possible risk factors, such as rates of smoking, obesity, hypertension, and lack of exercise. This data is available on a county-by-county level in the United States, so the research team aimed to match this physical epidemiology with their digital Twitter version.

Drawing on a set of public tweets made between 2009 and 2010, the researchers used established emotional dictionaries, as well as automatically generated clusters of words reflecting behaviors and attitudes, to analyze a random sample of tweets from individuals who had made their locations available. There were enough tweets and health data from about 1,300 U.S. counties, which contain 88% of the country’s population.

The researchers found that negative emotional language and topics, such as words like “hate” or expletives, remained strongly correlated with heart disease mortality, even after variables like income and education were taken into account. Positive emotional language showed the opposite correlation, suggesting that optimism and positive experiences, words like “wonderful” or “friends,” may be protective against heart disease.

“The relationship between language and mortality is particularly surprising,” co-author H. Andrew Schwartz said, “since the people tweeting angry words and topics are in general not the ones dying of heart disease. But that means if many of your neighbors are angry, you are more likely to die of heart disease.”

This finding fits into existing sociological research that suggests that the combined characteristics of communities can be more predictive of physical health than the reports of any one individual.

“We believe that we are picking up more long-term characteristics of communities,” co-author Lyle Ungar said. “The language may represent the ‘drying out of the wood’ rather than the ‘spark’ that immediately leads to mortality. We can’t predict the number of heart attacks a county will have in a given timeframe, but the language may reveal places to intervene.”

Limitations of the method’s predictive power include the social factors that influence what kinds of messages people choose to share on Twitter.

“If everyone is a little more positive on Twitter than they are in real life, however, we would still see variation from location to location, which is what we’re most interested in,” Schwartz said.

This variation could be used to marshal evidence of the effectiveness of public-health interventions on the community level, rather than on an individual level. The team’s findings show that these tweets are aggregating information about people that can’t be readily accessed in other ways.

“Twitter seems to capture a lot of the same information that you get from health and demographic indicators,” co-author Gregory Park said, “but it also adds something extra. So predictions from Twitter can actually be more accurate than using a set of traditional variables.”

The research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Pioneer Portfolio, through Exploring Concepts of Positive Health Grant 63597 (to M. E. P. Seligman), and by a grant from the Templeton Religion Trust.

All data and materials have been made publicly available via the Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/rt6w2/.

This article has received badges for Open Data and Open Materials. More information about the Open Practices badges can be found at https://osf.io/tvyxz/wiki/view/ and http://pss.sagepub.com/content/25/1/3.full.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.