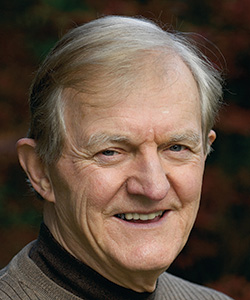

APS Past President Gordon H. Bower (1932-2020)

It is with great sorrow that we mark the passing of APS Past President Gordon H. Bower on June 17, 2020. A Charter Member of APS, he served as President from 1991-1993 and was a longtime psychology professor at Stanford University, where he influenced generations of scientists throughout the field. Among his many recognitions is the U.S. National Medal of Science, which he received in 2005.

See Bower’s 2009 Inside the Psychologist’s Studio interview.

See this longer tribute in the October Observer.

Bower’s student Mark Gluck, of Rutgers University, wrote the tribute that follows.

Born in a small town in Ohio, Gordon drew early inspiration from the movie The Lou Gehrig Story, resolving at the age of 8 to become a professional baseball player. By 11, he was good enough (and big enough) to play on local semi-professional teams. Although tempted by an offer to play professionally with the Cleveland Indians’ farm team, Gordon decided instead to attend Western Reserve University, where he played on the varsity baseball team. He also considered a career in psychiatry, until a summer job at the Cleveland State Mental Hospital, and the primitive state of psychiatric medicine at the time, dissuaded him. However, his interest in understanding mental disorders was undiminished, and he returned to college that fall with a new desire to pursue basic psychological research.

Graduating in 1954, Gordon had two career choices: professional baseball or graduate school in psychology. He entered the PhD program at Yale in the fall of 1955 and began working with advisor, Neal Miller, on electrical brain-stimulation studies in rats. In the summer of 1957, in turn, he won a fellowship to attend a workshop on mathematical learning theory at Stanford University, where he met Bill Estes and many other contributors to the burgeoning field of mathematical psychology. While attending that workshop, he so impressed Stanford faculty that they offered him a job even before he finished his PhD thesis, and in 1959 he moved to the faculty of the Stanford Psychology Department.

Trained as a behaviorist, Gordon established an extensive animal conditioning laboratory, including Skinner boxes that he built with circuits cannibalized from discarded pinball machines acquired from the local junkyard. By the mid-60s, however, Gordon’s animal research was crowded out by his growing interest in mathematical models of human learning.

Throughout his career, Gordon would identify a critical unsolved problem, make seminal contributions that established a new area of research, attract many other people to the new domain, and then move on to do it all over again in some completely different area of learning and memory research. Some of the vexing problems he addressed include: How do people reorganize memory during learning? How do mnemonic devices work? How does hypnosis affect memory? What role does mental imagery play in memory? How do we understand and remember simple narratives? How does our mood influence what we learn and remember? How do principles of animal conditioning apply to human category learning? Can connectionist network models, inspired by the brain, capture the richness of human cognition?

The breadth of Gordon’s reach can also be seen in the diverse (and almost conceptually opposite) spectrum of journals on whose editorial boards he served, including the leading journals of both Skinnerian behaviorism as well as the opposing cognitive psychology movement, and ranging from the most applied areas of clinical psychology to the most abstract realms of mathematical theorizing in psychology.

Importantly, Gordon’s considerable influence on the field of memory research stems not only from his own research but also from his role as a prolific educator and mentor to young psychologists, many of whom went on to play major roles in the growing fields of cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience.

In recent years, Gordon struggled with pulmonary fibrosis, which made it increasingly difficult for him to breathe. He passed away June 17 while sitting in his favorite chair at his home on the Stanford campus, surrounded by his wife, Sharon, his children, Lori, Tony, and Julia, and many of his grandchildren, all gathered together in anticipation of spending the upcoming Father’s Day with him.

Gordon never fulfilled his early dream of pitching a no-hitter at Yankee stadium; he spent his entire professional career at Stanford and retired to emeritus status in 2005. However, in his chosen career of psychology, he went up to bat time after time against a broad and diverse lineup of the most challenging problems in learning and memory, hitting a string of home runs worthy of his childhood idol, Lou Gehrig.

Mark Gluck is a professor of neuroscience at the Center for Molecular & Behavioral Neuroscience, and director of the Aging & Brain Health Alliance, at Rutgers University.

Comments

What a pleasure it was to meet and then work with Gordon during the early days of APS. As an applied organizational scientist, I had read some of his work and knew of his leadership in research.

On the sidelines of his first Board meeting, it was a delight to get acquainted and then hear his recollections about his career choice, including a baseball game played against my home team at Bowling Green State University.

I answered my office phone one day at a small college no one ever heard of, and a booming bass voice said “Hello, this is Gordon Bower.” I nearly fainted. Dr. Bower was the pinnacle of scientific genius, in my opinion, and I never thought I’d be important enough to talk with him. He asked my permission to use my recent memory book for students in his graduate seminar, explaining how much he liked the work. We emailed back and forth thereafter, but I will never forget that day he called and chatted with me like an old friend. “Hello, this is Gordon Bower.” Rest in peace, sir.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.