First Person

Student Notebook: Starting the Nonacademic Job Search After Graduate School

In recent years, academic positions have grown scarce as employment opportunities in nonacademic jobs—at least for individuals with doctoral degrees in psychology—have exponentially increased (Borland et al., 2019; McCave et al., 2020). Numerous nonacademic positions are available to psychology graduates in a range of fields, including industry, government, nonprofit organizations, and teaching outside the tenure-track (Stewart et al., 2021). Despite these various possibilities, many psychology graduate students are unaware of how to begin the job search. This is largely due to the minimal exposure students receive to these types of career paths and the equally slight support typically present within their respective departments for exploring alternatives to academia.

Thus, many students opt for a nonacademic career path with limited information and poor guidance. I aim to share information I’ve gathered through informal research on the topic. Specifically, I will focus on the steps to begin the nonacademic job search, including what I think are the most helpful job search engines and strategies. I hope this will be useful for students pursuing careers outside academia.

Where to begin?

There are several things to consider when exploring and executing a nonacademic job search. To start, most of the recent graduates and nonacademic resources I consulted recommend taking some time to assess your skills and interests to make the process easier and more meaningful (Chen, 2021; Rinker & Nahm, 2013).

Then begin researching and exploring job options using the search strategies most appropriate for the industry or industries that fit your area of research and interest. Gain more critical information about the current job market by reaching out to your network of psychology PhDs who have pursued nonacademic paths and attending nonacademic job panels (Cassuto & Jay, 2015).

Here’s a closer look at those steps, starting with assessing your interests, skills, strengths, weaknesses, and overall goals to better understand your area of interest and the kinds of opportunities you are seeking. Think of this in terms of identifying which aspects of your graduate program interest you the most—for example, conducting research, analyzing data, writing, presenting, or teaching. Use these insights to help you identify potential jobs within various nonacademic fields. In her blog, Amy Bucher (2014), vice president of behavioral design at a health systems company called Lirio, shared some job types recent psychology PhD graduates may be interested in outside of the academic tenure track, organized by individual interests. For instance, students interested in research may wish to look for jobs focusing on market research, user-experience research, or application development (e.g., at Headspace) or on industrial design research or research-based consulting (e.g., at Idea Couture Inc. from Cognizant), or jobs at technological companies (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Google, or Apple).

Search engines and strategies

Once you have a sense of the types of jobs available outside academia, it’s time to begin your search. A 2021 report by the Society for Social and Personality Psychology (SPSP) assessed the experience of recent psychology graduates and reported that they rated Indeed, Glassdoor, and LinkedIn as the most useful job search engines in finding their current positions. Other routes to consider include university career websites and doing a cold search via Google (Clair et al., 2017; Kyllonen, 2004).

The SPSP report also showed that applicants found particular keywords most helpful in their job search, including advocacy, data, behavioral, policy, and program evaluation. (See the word cloud in Figure 1 for a full list of the cited keywords.)

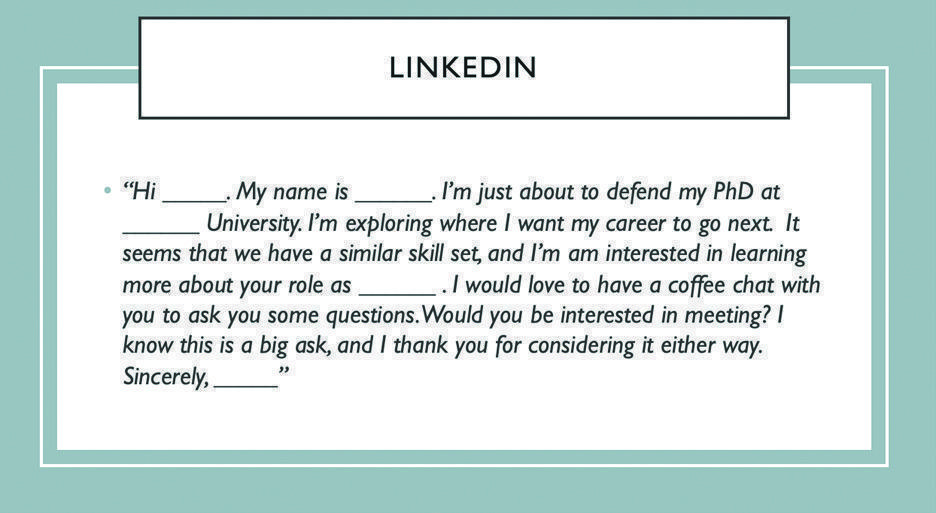

Taking a closer look at LinkedIn, Chris Cornthwaite, who has a PhD in religious studies and publishes the blog Roostervane, suggested that its real power is the ability to highlight multiple aspects of yourself. Thus, it is important to present a complete LinkedIn profile including your experiences, education, skills, etc. (Borland et al., 2018). Then use LinkedIn to connect with as many individuals, within your career of interest, as you can. Another way to maximize your time on LinkedIn is to connect with individuals in positions you might aspire to be in and conduct informational interviews.

In Figure 2, I present a template of a message you could send when inviting someone for a coffee chat or informational interview. In addition to conducting informational interviews and building a network as an informal road to a nonacademic position, recent graduates recommend volunteering for an organization you may be interested in working for in the future, completing a practicum sometime in the 4th year of your PhD to maximize the possibility of being hired once you graduate, and following organizations or associations within your area of research through Twitter and LinkedIn (Borland et al., 2018; Snow, 1994).

I hope these tips can assist fellow psychology students in getting started with their nonacademic job searches. Even though I am most interested in pursuing a career in academia, I strongly believe that students should be provided with the right tools and information to pursue a career in any area after leaving graduate school. In the final year of my PhD, I plan to apply many of the above tips in my search for both a practicum position and a full-time position, mainly focusing on networking through LinkedIn and conducting informational interviews. I wish you luck in looking beyond the graduate experience!

Menahal Latif ([email protected]) is a PhD student in psychology at Ryerson University working under the supervision of Margaret Moulson at the Brain and Early Experiences Lab. Her research interests include face perception and emotion regulation in adults, children, and infants.

This article was initially published in the print edition of the May/June 2022 Observer under the title, “From Graduate School to Industry: Starting the Nonacademic Job Search.”

Student Notebook serves as a forum in which APS Student Caucus members communicate their ideas, suggestions, and experiences. Read other Student Notebook columns here, and learn about the benefits of Student Membership.

Interested in submitting a Student Notebook article of your own? Learn more and indicate your interest by clicking here (logged-in APS members only).

Feedback on this article? Email [email protected] or scroll down to comment.

References

Borland, K. M., LaMarco, T., & Longhi, A. H. (2018). Preparing for and conducting job searches outside academia. In J. B. Urban & M. R. Linver (Eds.), Building a career outside academia: A guide for doctoral students in the behavioral and social sciences (pp. 135–149). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000110-013

Bucher, A. (2014, August 21). Career options outside academia for psychology PhDs. https://www.amybucherphd.com/career-options-outside-academia-for-psychology-phds/

Cassuto, L., & Jay, P. (2015). The PhD dissertation: In search of a usable future. Pedagogy, 15(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-2799212

Chen, S. (2021). Leaving academia: Why do doctoral graduates take up non-academic jobs and to what extent are they prepared? Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 12(3), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-08-2020-0057

Clair, R. S., Hutto, T., MacBeth, C., Newstetter, W., McCarty, N. A., & Melkers, J. (2017). The new normal: Adapting doctoral trainee career preparation for broad career paths in science. PLoS ONE, 12(7): e0181294. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177035

Kyllonen, P. C. (2004). Broadening the job search: Jobs outside of academia. In J. M. Darley, M. P. Zanna, & H. L. Roediger, III, The compleat academic: A career guide (2nd ed, pp. 57–76). American Psychological Association.

McCave, E. J., Bodnar, C. A., Smith-Orr, C. S., Strong, A. C., Lee, W. C., & Faber, C. J. (2020). I graduated, now what? An overview of the academic engineering education research job field and search process [Paper presentation]. ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, virtual (online). https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2–34741

Rinker, C., & Nahm, S. (2013). Stress, survival, and success in Academia 2.0: Lessons from working inside and outside of the academy. Practicing Anthropology, 35(1), 40–43. https://doi.org/10.17730/praa.35.1.m03u118587530v6j

Snow, J. E. (1994). Ph.D.: Asset or liability? In Eos, 75(34), 388–388. https://doi.org/10.1029/94EO01032

Stewart, D., Vu, H., Austin, K., Andrade, F., Tissera, H., Conrique, B., & Vuletich, H. (2021). Careers outside of academia for social and personality psychologists: Strategies and insights about the non-academic job market. Society for Personality and Social Psychology. https://spsp.org/sites/default/files/Strategies_and_Insights_about_the_Non-Academic_Job_Market_Technical_Report.pdf

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.