A Bias Against Creativity?

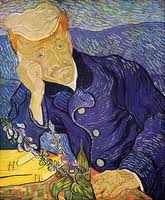

Vincent Van Gogh may be the most famous unappreciated artist of all time. Indeed, he was a failed painter, selling only two of his more than 2000 works during his lifetime. Yet his vibrant post-Impressionist style would influence generations of painters to come, and nowadays few would dispute his creative genius. His Portrait of Dr. Gachet sold some years ago for $82.5 million.

Vincent Van Gogh may be the most famous unappreciated artist of all time. Indeed, he was a failed painter, selling only two of his more than 2000 works during his lifetime. Yet his vibrant post-Impressionist style would influence generations of painters to come, and nowadays few would dispute his creative genius. His Portrait of Dr. Gachet sold some years ago for $82.5 million.

Van Gogh is in good company. El Greco was scorned by critics, and Johannes Vermeer died in obscurity. Similarly, the writers Henry David Thoreau, Edgar Allan Poe and Franz Kafka—all innovators—received little in the way of honors or recognition in their own eras.

This is a puzzle. It’s not like we don’t value creativity—the opposite really. Ask anyone what they think of creativity, and they’ll likely put it in that category with babies and laughter and rainbows—a universal good. Yet even though we embrace creativity in the abstract, we reject so many innovative and novel ideas. There are no doubt Van Goghs and Kafkas experiencing rejection right at this moment.

University of Pennsylvania psychological scientist Jennifer Mueller was curious about this paradox. She and her colleagues wondered whether the novelty of truly creative ideas might lead to a state of uncertainty that’s psychologically uncomfortable. If so, she reasoned, then humans might be secretly—unconsciously—biased against creative ideas. She decided to explore this heretical idea in the laboratory.

She recruited a group of volunteers, who she paid for their participation. The payment is important, because she told half of them that they might get more money, depending on a random lottery. This manipulation was intended to create a sense of psychological uncertainty in half the volunteers. She was simulating the uncomfortable uncertainty produced by novel ideas, which can be seen as impractical and unreliable and threatening. Following this manipulation, all of the volunteers took two attitude tests: The first measured their explicit attitudes toward creativity and practicality, to see if they had any overt bias one way or the other. The second test tapped into their unconscious mental associations with creativity and practicality.

When she crunched the data together, the results were provocative. There was no difference in the volunteers’ stated attitudes toward creativity. That’s not surprising, since everyone loves creativity in theory. But the volunteers who were primed for uncertainty were clearly ambivalent about creativity and practicality. Despite their overt endorsement of creative thinking, they revealed much more of an unconscious anti-creativity bias than the others. And the bias was not subtle: These volunteers unconsciously linked creativity with words like “agony” and “poison” and “vomit.”

Mueller wanted to reexamine these findings in a slightly different way, focusing on problem solving. It’s believed that the most effective problem solvers generate lots of novel ideas—what’s known as brainstorming—and then identify the single best option from the lot. This second step—settling on the optimal solution—reduces the psychological uncertainty connected to having many choices in flux. This focus on the best answer creates motivation to clear away uncertainty—and thus an anti-creativity bias.

At least that’s the theory, which Mueller tested in a second experiment. This time she primed half the volunteers to be tolerant of ambiguity, and the other half to be intolerant. After this manipulation, all the volunteers again took the two attitude tests. But Mueller added another test—one designed to see if the volunteers could actually recognize a creative idea. She asked them about an idea that had been pre-tested and rated as highly creative: A running shoe with nanotechnology that adjusted fabric thickness for cooling and foot protection.

The results were clear, and consistent with the earlier results. Again, there was no difference in explicit attitudes toward creativity. But as described in a forthcoming issue of the journal Psychological Science, those who had been primed to be intolerant of ambiguity showed a stronger unconscious bias against creativity. What’s more, those with low tolerance for uncertainty—that is, more need for closure and predictability—rated the innovative running shoe as less creative. These are no doubt the same people who turned their noses up at Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet.

This unconscious bias operates beyond the world of art. Mueller points to the example of Robert Goddard, now widely acknowledged as the father of modern rocketry, whose ideas were ridiculed by his scientific peers. Regardless of how open-minded we are, we are all shaped by a powerful psychological bias for clarity and certainty—a bias that links creativity with negativity. Ironically, uncertainty spurs us to search for innovative answers, but this same uncertainty makes us blind to truly creative ideas when we see them.

Excerpts from Wray Herbert’s two blogs—“We’re Only Human” and “Full Frontal Psychology”—appear regularly in Scientific American Mind and The Huffington Post. His book, On Second Thought, will soon be out in paperback.

Comments

Unique and fascinating deductions by researcher Dr. Jennifer Mueller. Want to know more about her and her work.

Business negotiator, Katharine Walch

Creative solutions have to be novel and effective. If something is novel it is therefore also untried, and the effectiveness may be difficult to judge before hand. Creative solutions imply a higher level of risk, and perhaps more scorn and ridicule if they fail. Truly novel solutions are often proposed by outsiders who are themselves regarded as untried and unknowns.

Another inhibition to creativity can be the egos of the keepers of the conventional wisdom. A new and creative solution may have to change or displace both the old solution and the old order.

The research demonstrated that the circumstances and environment highly influence whether creative ideas will have a chance.

I have a great respect for those who can look at truly creative solutions and recognize them for what they are. Great leaders are often people who may not be creative themselves, but they know a good idea when they see one.

Bart Schuster

Arrive2.net

Twitter.com/arrive2_net

SO TRUE! I feel the more creative an idea (doesn’t have to be from me) is the most hated in my organization. Tried and true is comfortable for most…they’d rather stick with the status quo than be creative.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.