Practice

Teaching: Personality Stability and Change / Building Cultures of Sustainability

Edited by C. Nathan DeWall

Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science offers advice and guidance about teaching a particular area of research or topic covered in this peer-reviewed APS bimonthly journal, which features reviews covering all of scientific psychology and its applications.

Understanding Personality Stability and Change

Building New Cultures of Sustainability

Understanding Personality Stability and Change

By C. Nathan DeWall

In November 2020, the Atlantic published a sensational article that identified a hidden network of wealthy parents who urged their children to pursue niche sports (fencing, crew, squash) to gain admission to Ivy League universities. The article represented a second chance for its author, Ruth Shalit Barrett, whose reporting career had been wrecked amid allegations of plagiarism in the 1990s. But shortly after the Atlantic published Shalit Barret’s comeback article, readers expressed concern regarding its accuracy. Eventually, the Atlantic retracted the article, noting that “the author misled our fact-checkers, lied to our editors, and is accused of inducing at least one source to lie to our fact-checking department.” Once dishonest, always dishonest?

Not necessarily, according to Jenny Wagner, Ulrich Orth, Wiebke Bleidorn, Christopher Hopwood, and Christian Kandler, who present an integrative framework for understanding personality stability and change. They argue that personality predicts important life outcomes, but it also shifts over time (Bleidorn et al., 2019; Soto, 2019). Instead of asking whether personality changes, personality researchers should spend their time explaining why some personality traits change and others remain stable.

Our genes and environment contribute to our personality (Bleidorn et al., 2014). Yet no single genetic mutation or environmental event reliably alters personality. Instead, Wagner and colleagues (2020) emphasize that “people are often agents of their own stability and change” (p. 439). For example, introverts typically pursue environments that sustain their social motivation without sapping their energy, rather than social situations that would demand more extraversion. Conversely, people who strive to increase their conscientiousness may pursue careers that require reliability, carefulness, and diligence (Hudson & Fraley, 2016).

Students enjoy completing personality tests, so you should have no problem generating discussion. The following activity will encourage students to complete a brief personality inventory, followed by some reflection exercises. I recommend presenting the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (Gosling et al., 2003) on PowerPoint slides.

Instructions:

Here are a number of personality traits that may or may not apply to you. Please write a number next to each statement to indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with that statement. You should rate the extent to which the pair of traits applies to you, even if one characteristic applies more strongly than the other.

Ten-Item Personality Inventory

I see myself as:

Extraverted, enthusiastic.

Critical, quarrelsome.

Dependable, self-disciplined.

Anxious, easily upset.

Open to new experiences, complex.

Reserved, quiet.

Sympathetic, warm.

Disorganized, careless.

Calm, emotionally stable.

Conventional, uncreative.

Scoring instructions (“R” denotes reverse-scored items): Extraversion: 1, 6R; Agreeableness: 2R, 7; Conscientiousness; 3, 8R; Emotional Stability: 4R, 9; Openness to Experiences: 5, 10R

Ask students to complete the Ten-Item Personality Inventory and then score their responses. Make sure that students understand how to reverse-score items. Next, ask students to answer some reflection questions with a discussion partner. If you are teaching in a face-to-face format, make sure that students are using appropriate social distancing. If you are teaching virtually, you can put the students in breakout rooms.

Have students respond to the following discussion prompts:

- Which of the five personality traits have shown the most stability over your lifetime? Describe situations that inform your judgment about which of your personality traits seem the most stable.

- Which of the five personality traits seem the least stable over your lifetime? How has your personality changed along these dimensions?

Wagner and colleagues argue that people are often agents of their personality stability and change. Looking at your answers to the first two prompts, what actions have you taken to increase your personality trait stability? What steps have you taken to change certain personality traits?

Personality matters mightily. People should recognize and respect personality’s power to predict important life outcomes—from finding a compatible romantic partner to finding a fulfilling career. Although personality is often considered unchangeable, it shifts across the life span and in response to life events. By understanding personality stability and change, students can better understand themselves, their fellows, and their global community.

References

Bleidorn, W., Hill, P., Back, M., Denissen, J. J. A., Hennecke, M., Hopwood, C. J., Jokela, M., Kandler, C., Lucas, R. E., Luhmann, M., Orth, U., Wagner, J., Wrzus, C., Zimmermann, J., & Roberts, B. (2019). The policy relevance of personality traits. American Psychologist, 74(9), 1056–1067.

Bleidorn, W., Kandler, C., & Caspi, A. (2014). The behavioural genetics of personality development in adulthood—Classic, contemporary, and future trends. European Journal of Personality, 28(3), 244–255.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528.

Hudson, N. W., & Roberts, B. W. (2016). Social investment in work reliably predicts change in conscientiousness and agreeableness: A direct replication and extension of Hudson, Roberts, and Lodi-Smith (2012). Journal of Research in Personality, 60, 12–23.

Soto, C. J. (2019). How replicable are links between personality traits and consequential life outcomes? The Life Outcomes of Personality Replication Project. Psychological Science, 30(5), 711–727.

Shalit Barrett, R. (2020, November). The mad, mad world of niche sports among Ivy League–obsessed parents. The Atlantic. https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/files/20201101_nichesports.pdf

Building New Cultures of Sustainability

By David G. Myers

In 1960, Spaceship Earth carried 3.0 billion people with 127 million motor vehicles. Today, with 7.8 billion people and 1.3 billion motor vehicles, greenhouse gases are accumulating, and Earth’s climate is under assault. As multiple scientific reports document (National Aeronautics and Space Administration, n.d.),

- sea and air temperatures are rising,

- plant and animal life is migrating northward or upward,

- snow and ice packs are melting,

- the seas are rising, and

- extreme weather—fires, hurricanes, droughts, floods—is increasing.

With the feared climate future now approaching, we can appreciate a recent Internet meme: “Goodnight moon. Goodnight Zoom. Goodnight sense of impending doom.”

For more on sustainability, see this collection of articles on climate change.

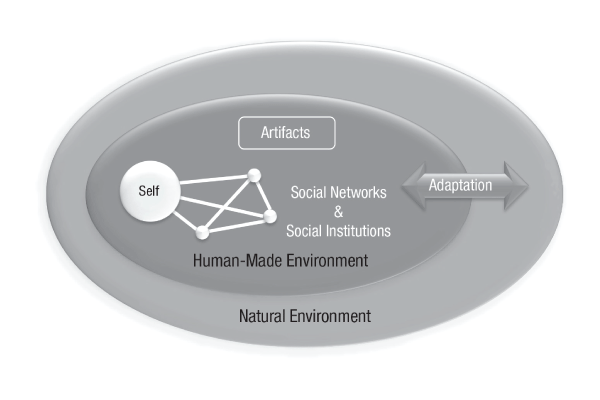

If the bad news is that climate change is a likely weapon of mass destruction, the good news, reports Melbourne University social psychologist Yoshihisa Kashima, is that Homo sapiens has survived and flourished thanks to culture. Humans have adapted to varied environmental niches throughout our species’ existence. From the Equator to the Arctic, through the 14th century Little Ice Age and other environmental changes, humans have constructed dwellings, social networks, and institutions that have sustained our species. Thanks to culture—the socially shared information, attitudes, traditions, and inventions transmitted across generations—we are able to build on accumulated knowledge.

What is more, culture can change. And that allows us to envision future “cultures of sustainability,” observes Kashima. “New cultures may form. If a culture of human-nature disconnect has emerged over the 20th century, cultures of sustainability may emerge over the 21st.”

Kashima believes the recipe for such cultural transformation has four ingredients:

- Reconceiving the human-nature relationship. Instead of seeing themselves as distinct from nature, and nature as a resource to be used indiscriminately, people in cultures of sustainability will “include nature as an important part of themselves.” Humans will share and practice ideas of “human-nature connectedness.”

- Reconceiving human-artifact relations. The present-day linear conception of mass produce à consume à discard will be recrafted into a circular conception of assemble à recycle à reconfigure.

- Norms and regulations that sustain the global commons. We are living the tragedy of the commons, as individuals, organizations, and countries pursue their self-interest to everyone’s collective detriment. Future cultures of sustainability will, therefore, entail both shared climate-friendly norms and government policies that incentivize collective conservation and renewable energy.

- Envisioning a green utopia. Although our “system justification” serves to sustain the status quo, there is also a power to utopian thinking—to imagining an ideal future. Goals matter. They direct attention, promote effort, motivate persistence, and stimulate creativity (Gollwitzer & Oettingen, 2012). Moreover, goals are often realized when people mentally contrast a desired future with likely obstacles and form “implementation intentions” (if-then plans) that specify how they will overcome those obstacles (Oettingen & Gollwitzer, 2019). Thus, says Kashima, a shared green utopia might “motivate pro-environmental behaviors” and accelerate a global cultural trend toward a sustainable future.

The possibilities for student engagement with this topic are plentiful and can include small group or class discussion questions, such as the following:

- Where does climate change rank on your list of national and world problems?

- What principles of persuasion might strengthen ideas of human-nature connectivity and associated social norms and practices?

- What psychological forces drive cultural change?

As a writing assignment, instructors might also invite students to articulate their vision of a utopia—a North Star ideal that could help us navigate our future. Such a society might protect both lives and livelihoods, respect human rights and support human aspirations, define life success and satisfaction in nonmaterial terms, pursue truth with openness to mystery, provide both connection and purpose, supplement “me thinking” with “we thinking,” and live gently upon our Earth.

Kashima reminds us that, despite threatening climate trends, humans have the power to “craft cultures of sustainability.” Moreover, our species’ past successes in adapting to varied environments, and our increasing climate awareness, give us hope. As Rory Cooney’s “The Canticle of the Turning” chorus concludes, “Wipe away all tears, for the Dawn draws near, and the world is about to turn!”

References

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Oettingen, G. (2012). Goal pursuit. In P. M. Gollwitzer & G. Oettingen (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 208–231). Oxford University Press.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (n.d.). Scientific consensus: Earth’s climate is warming. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from climate.nasa.gov/scientific-consensus

Oettingen, G., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2019). From feeling good to doing good. In J. Gruber (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of positive emotion and psychopathology; The Oxford handbook of positive emotion and psychopathology (pp. 596–611). Oxford University Press.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.