Amazon’s Mistake: Mixing Creative Conflict With Animosity

“Of all [Jeff Bezos’] management notions, perhaps the most distinctive is his belief that harmony is often overvalued in the workplace — that it can stifle honest critique and encourage polite praise for flawed ideas. Instead, Amazonians are instructed to “disagree and commit” (No. 13) — to rip into colleagues’ ideas, with feedback that can be blunt to the point of painful, before lining up behind a decision.”

“Of all [Jeff Bezos’] management notions, perhaps the most distinctive is his belief that harmony is often overvalued in the workplace — that it can stifle honest critique and encourage polite praise for flawed ideas. Instead, Amazonians are instructed to “disagree and commit” (No. 13) — to rip into colleagues’ ideas, with feedback that can be blunt to the point of painful, before lining up behind a decision.”

– New York Times

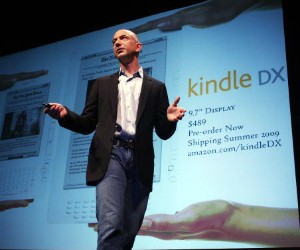

Amazon’s CEO Jeff Bezos may want to read up on some new findings from psychological science: conflict can enhance creativity, but not all conflict is good for business.

Teams can benefit from looking at a problem with a critical eye, even if that means someone’s feelings get hurt in the process. However, research has also shown that not all conflict is created equal; once conflict gets personal, it begins to eat away at team members’ motivation and productivity.

In a new study, a team of Canadian psychological scientists led by Thomas A. O’Neill of the University of Calgary identified four distinct patterns of team conflict—some forms of conflict boosted performance, while others sapped it.

Researchers who study team conflict have identified three distinct types: task conflict, relationship conflict, and process conflict. In task conflict, people debate the details of how to accomplish a goal. Relationship conflict occurs when things get personal; team members clash personally and feel anger, animosity, and resentment towards each other. Process conflict occurs when individuals disagree about how to execute a goal, such as who should do what.

There’s some evidence that task conflict can benefit teams. Just like Bezos suggests, encouraging divergent perspectives allows teams to more effectively tackle a problem. However, O’Neill and colleagues suspected that situations that had high task conflict, but also intense interpersonal drama and relationship conflict, would drain cognitive resources and diminish performance.

“Team members will more likely experience depleted attention, energy, and effort for the task because of the need to divert cognitive resources so as to manage the feelings of fear, threat, and distrust,” the researchers write in the Journal of Management.

To find out how one style of conflict might bleed into other areas, the researchers observed a group of 577 1st-year engineering students. For a class, the students were organized into 195 teams that worked together throughout the 13-week semester to complete a series of engineering design projects. Each individual students’ grades for the class were based on team projects such as building a sailboat, a racecar, a biomimetic design, and a video game.

Just before the end of the semester, each student answered a series of questions about their team. They were asked about how much teammates debated, how much friction there was among team members, and how often they disagreed about who should do what. They were also asked a series of questions about how productive they felt and how cooperative the team was.

The results showed that there were four distinct profiles of team conflict ranging from high levels of beneficial task conflict to high levels of destructive interpersonal conflict. A key finding was that task conflict contributed to strong performance on complex tasks—as long as it occurred in an environment free of interpersonal discord.

Importantly, productive conflict tended to decrease as interpersonal conflict increased. This suggests that as interpersonal frictions arise, people become wary of expressing the divergent viewpoints that can make conflict valuable for teams.

By encouraging uncompromising competition among team members, Amazon’s management may have unwittingly fostered a form of conflict that actually killed worker innovation.

Further research on these patterns of conflict could be used to help identify and reverse problems– before they reach Amazonian proportions.

Reference

O’Neill, T. A., McLarnon, M. J., Hoffart, G. C., Woodley, H. J., & Allen, N. J. (2015). The Structure and Function of Team Conflict State Profiles. Journal of Management. doi: 10.1177/0149206315581662

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.