Why Your Understanding of Collectivism Is Probably Wrong

Imagine you’ve won a 2-week, all-expenses-paid trip to a faraway country. You don’t know where you’re going, but they tell you it’s a collectivistic culture. What images come to mind?

Are the people warm and caring? Are they helping and cooperative? Do they feel close to their friends and family?

If that’s your intuition, you’re not alone. It was the intuition tucked away in my brain when I moved to Beijing. Many PhD-holding cultural psychologists have it, too. It’s built into our measures.

A Simple Task: Measuring Collectivism

In the ‘90s, cultural psychologists, most of whom were based in North America and Europe, designed surveys to measure collectivism across cultures (e.g., Singelis, 1994). They wrote statements that collectivists should agree with:

- “I feel good when I cooperate with others.”

- “I like sharing little things with my neighbors.”

After the scales were written, the next step was to make sure they were reliable. In short time, the surveys passed tests of statistical reliability. People who agreed with “I feel good when I cooperate with others” also tended to share things with their neighbors. So far so good.

Armed with reliable tests, researchers set out to study cultures across the Pacific Ocean. They started by documenting differences in collectivism that experts were pretty sure were there (e.g., Heine, Lehman, Peng, & Greenholtz, 2002). Given what researchers already knew, Japan and China should be more collectivistic than America and Western Europe, they thought.

Cultural Psychology’s Open Secret

Within 20 years, researchers had completed enough studies that they could put them all together and meta-analyze them. What they found seemed plain wrong.

America, land of the cowboy, was more collectivistic than Japan (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002). What about the Philippines and Tanzania? Americans were more collectivistic than people from both of those countries. Attempts to find reliable differences between East and West were no different (statistically) than flipping a coin (Heine et al., 2002).

Perhaps the data were right and people’s expectations were wrong — maybe Japan and China aren’t actually collectivistic. This explanation is particularly tempting 20 years later, after China’s meteoric economic growth.

The Fault in Our Microscopes

Yet most of the reactions avoided that tack. Instead, researchers suggested it was a problem of self-report methodology — after all, there’s evidence to suggest that people just aren’t very good at making accurate self-reports.

For example, researchers produced good evidence that people in Japan implicitly compare themselves with other (presumably collectivistic) Japanese people, which lowers their estimation of their own collectivism (Heine, Lehman, Peng, & Greenholtz, 2002).

Other researchers pinpointed the problem in how people use scales (e.g., Schimmack, Oishi, & Diener, 2005). The idea was that people in some cultures just tend to agree more — they’re more acquiescent. They’ll agree with “I often ‘do my own thing’” and “To me, pleasure is spending time with others,” even though researchers designed the two statements to measure two opposite attitudes. To solve this problem, researchers would need to adjust their analyses, statistically controlling for how much people tend to agree.

Still others said the problem was that the wordings are too abstract. Doing “my own thing” could mean wearing red shoes for a high schooler in Shanghai but could mean living alone for 30 years for a New Yorker. To fix this, researchers said the solution was to write scales about concrete scenarios (Peng, Nisbett, & Wong, 1997).

What all of these responses had in common was that they diagnosed the problem as residing in the measurement tool — the problem was in our microscopes. If we could fix our microscopes, we could get to the truth.

Maybe the Problem Is Us

But there’s another thing these explanations have in common: They’re about our microscopes, not our concepts. And it’s problems with our concepts that recent evidence is pointing to.

Scattered hints were already there for researchers who looked in the right places. One hint was in the writings of a Japanese anthropologist who spent time living in rice-farming villages (Yoshida, 1984). In the village, tight ties and shared irrigation water created both harmony and conflict. The harmony was needed to keep the water flowing to the fields, but the harmony existed partly to obscure the conflict. “Tensions lie below the surface, feelings run deep, grudges persist, but the surface of relationship is managed to exhibit harmony.”

Another hint could be found far away in Ghana. There in West Africa, a psychologist documented widespread “enemyship” (Adams, 2005). Compared with individualistic Americans, people in Ghana were much more likely to believe that their friends were secretly plotting against them. One local book warned that your most intimate friends may be “actually at the helm plotting your downfall” (Kyei & Schreckenbach, 1975).

Pieces That Don’t Fit

And evidence continues to accumulate, suggesting that these are not rare exceptions to collectivism but rather a common feature of collectivism itself. In a study just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, my colleagues and I found that people in collectivistic China were more likely than Americans to be vigilant toward fellow in-group members (Liu, Morris, Talhelm, & Yang, 2019). Participants read about, for example, an eager coworker who offered to help them look over an important work project and then wrote about what might happen next. Some people worried that the coworker would be up to no good: “The friend also ‘accidentally’ threw some of the pages into the trash . . .. His friend did not want to see [him] be successful and be promoted.”

This worried vigilance colored 38% of responses from participants in China versus just 16% of responses from those in the United States.

And this vigilance exists despite the fact that Chinese participants rated coworkers as more of a family, with more of a shared identity, than American participants did. People in China were indeed more collectivistic, but that collectivist tendency didn’t entail trust.

The emerging theory is not that this tension exists despite collectivism; rather, this tension exists because of collectivism. The tight social ties of collectivism creates this tension.

The Vigilance of Rice

Of course, there are many other differences between China and the United States. For one, China scores higher on measures of corruption — data available from Transparency International (n.d.). China also endured the Cultural Revolution, which had the effect of pitting neighbors against neighbors and left lasting influences on people’s willingness to trust others (Wang, 2017). These alternative explanations fit nicely.

To dig deeper into these possible explanations, the authors of the vigilance study have also compared regions within China. Within the same national political system, Han China is split into two major cultural regions. In the south, people have farmed paddy rice for generations. In the north, wheat was the dominant crop. Rice farmers had to coordinate irrigation networks and muster twice the amount of labor per hectare that wheat farmers did (Talhelm & Oishi, 2018). Rice was, therefore, a more collective crop.

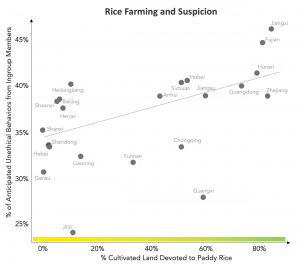

To this day, people in rice areas show more hallmarks of collectivism than people in wheat areas (Talhelm et al., 2014). And in these collectivistic rice regions, people were more vigilant toward their peers than people in wheat areas. The differences weren’t in the national political system; instead, they fell along the geographical boundaries of collectivism. See Figure 1.

De-Idealizing Collectivism

The emerging picture of collectivism is less warm and fuzzy, more nuanced and complicated. And, as it turns out, this picture was already hidden in the early collectivism scales.

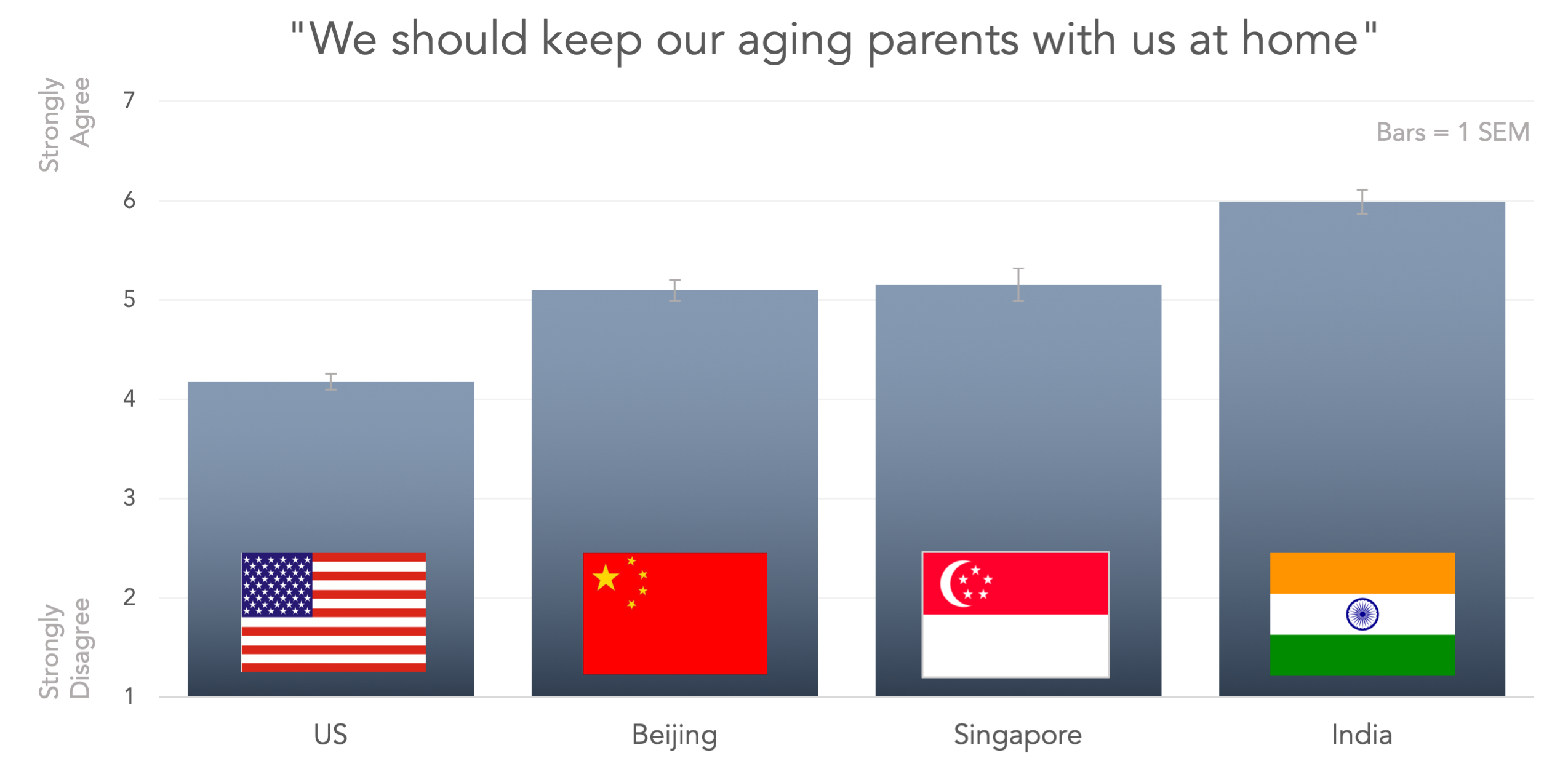

Tucked in among the warm-fuzzy items that didn’t “work,” there were also items that did work. The items that worked mostly asked about duties and responsibilities to specific people. For example, my recent research has found that people in collectivistic cultures are more likely to agree that “We should keep our aging parents with us at home.” See Figure 2.

And although people living in collectivistic cultures report less intimacy with their friends, they are also more likely to think that they should stick together through tough times (Liu et al., 2019). When I asked people to imagine a friend advising them to break up with a new boyfriend, Americans tended to say they’d find more supportive friends. In China, people tended to think these friends were being supportive. Collectivism often values things other than warmth and feeling good.

The emerging picture of collectivism is more complicated and, I think, realistic. If this vision is correct, it suggests that the answer to cultural psychology’s open secret lies more in asking the right questions than in throwing out self-reports.

Figure 1

The chart shows that in areas of China where rice farming is widespread — and coordination and networking more necessary — people are more suspicious of their peers compared to areas where rice farming is less extensive. This reflects the distrust that people of China can harbor toward one another despite their collectivist tendencies.

Figure 2

Recent research shows that the more collectivist a culture tends to be, the more people feel a duty to take in their aging parents.

References

Adams, G. (2005). The cultural grounding of personal relationship: Enemyship in North American and West African worlds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 948–968. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.948

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Peng, K., & Greenholtz, J. (2002). What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales? The reference-group effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 903–918.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.903

Kyei, K. G., & Schreckenbach, H. (1975). No time to die. Accra, Ghana: Catholic Press.

Liu, S., Morris, M. W., Talhelm, T., & Yang, Q. (2019). Ingroup vigilance in collectivistic culture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 116, 14538–14546.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1817588116

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3

Peng, K., Nisbett, R. E., & Wong, N. Y. (1997). Validity problems comparing values across cultures and possible solutions. Psychological Methods, 2, 329–344.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.2.4.329

Schimmack, U., Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2005). Individualism: A valid and important dimension of cultural differences between nations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0901_2

Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 580–591.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205014

Talhelm, T., & Oishi, S. (2018). How rice farming shaped culture in Southern China. In A. K. Uskul & S. Oishi (Eds.), Socioeconomic environment and human psychology (pp. 53–76). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3199657

Talhelm, T., Zhang, X., Oishi, S., Chen, S., Duan, D., Lan, X., & Kitayama, S. (2014). Large-scale psychological differences within China explained by rice versus wheat agriculture. Science, 344, 603–608.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1246850

Transparency International. (n.d.). China. Retrieved from

https://www.transparency.org/country/CHN

Wang, Y. (2017). For whom the bell tolls: The political legacy of China’s Cultural Revolution. Retrieved from

https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/yuhuawang/files/cultural_revolution_0.pdf

Yoshida, T. (1984). Spirit possession and village conflict. In E. Krauss, T. Rohlen, & P. Steinhoff (Eds.), Conflict in Japan (pp. 85–104). Honolulu: University of Hawaii.

Comments

This reframing makes a great deal of sense subjectively if one contrasts, say, rice-cultivating Kerala where (in my experience) suspicion can rise to the level of intrigue, versus wheat-cultivating Haryana where suspicion is more straightforwardly and egalitarianly applied. Of course, there’s a lot of trust and mutual support in both these cultures, but somehow Kerala feels wrapped more tightly, constrained by networks of formulaic obligations of family and community relationships, and correspondingly more wary about individuals’ true intentions beyond these formal obligations. I’ve experienced “moral policing” in Kerala but not in Haryana (though it does of course exist there). And the same high construal and psychological distance that make these cultures so good at communal support also make them ruthless at communal ostracism. I wonder why so much of the study of collectivistic cultures uses only China as an example when India too offers a wealth of instances and contrasts.

I really like this explanation of our perception of the collectivist perspective- I would love to see new comparative data taken in the next few months in eastern and western cultures, now that the pressures of COVID-19 are being felt worldwide!

This is an interesting perspective on the nuances of collectivism. Cultural values, like culture itself, are not static and exist on a wide spectrum even within smaller group clusters. It would have been informative to consider how globalization influences the shift in cultural standpoints, and whether individualistic ideals are inherent or imported. Nonetheless, this is a pretty compelling read in that it demonstrates the nuances in cultural dispositions and value differences.

This commentary sounds very reasonable. However, I have one reservation or suspicion, which has been raised in the tradition of INDCOL research. Some studies indicates that the term ‘family’ or its implication has some confounding effect among many items of INDCOL. Do you think the concept, familism or familialism should be separate from collectivism. To my knowledge, the item “We should keep our aging parents with us at home” has been used for measuring Hispanic familism. We are planning to do the survey on Italy comparing the North and South. Your advice will be much appreciated. Thank you.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.