APS Spotlight

Remarkable Resiliency: George Bonanno on PTSD, Grief, and Depression

Whether illness, disaster, or death of a loved one, most of us go through at least one traumatic event in our lifetimes. The dramatic nature of these experiences has driven psychological scientists to focus on the damage these challenges can cause, particularly in the areas of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), prolonged grief disorder, and major depressive disorder, according to researcher George A. Bonanno — but there’s more to the picture.

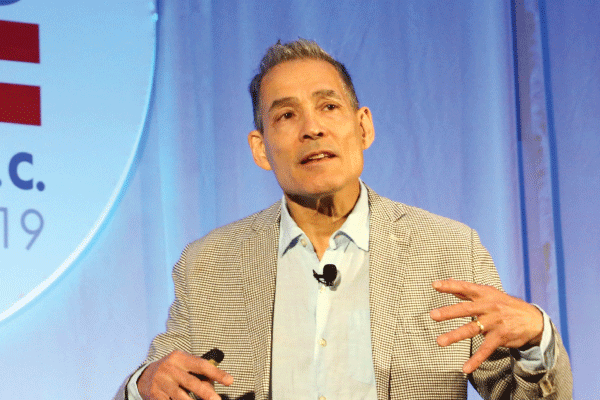

“I would argue we can’t really understand psychopathology if we don’t understand the rest of the responses, the normative response,” said Bonanno, a professor of clinical psychology at Teacher’s College, Columbia University, during his James McKeen Cattell Fellow Award Address at the 31st APS Annual Convention last spring in Washington, DC.

Resiliency in the face of traumatic events is often assumed to be rare, to the point that those who don’t have a marked reaction to loss or suffering may even be said to be lying to themselves, or otherwise repressing their emotions, Bonanno explained. In reality, people are often remarkably resilient.

In a Psychological Science survey of 2,752 New Yorkers, Bonanno and colleagues found that 65% of participants reported one or no symptoms of PTSD 6 months after the September 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center. Furthermore, more than half of those who were involved with the 9/11 rescue effort or were in or near the World Trade Center during the attack also reacted with relative resilience, reporting few or no symptoms of PTSD.

A meta-analysis by Bonanno and colleagues of 54 studies on individuals’ well-being in the wake of potentially traumatizing events, including injury, bereavement, natural disaster, and combat experience, confirmed these results: 65% of people showed a trajectory of few or no symptoms of psychopathology related to the event.

“That resilience trajectory is not only most common, it’s the majority,” Bonanno said.

Similar trajectories are present in animal models as well, Bonanno noted. Rats who have been shocked while listening to a tone continue to exhibit freezing behavior in response to the sound, even when it is no longer accompanied by pain, he explained. But while rats appear to acquire fear at a relatively consistent rate, Bonanno and colleagues found significant variability in how long it can take for this fear to be extinguished. In a set of 58 rats, 57% stopped reacting to the tone after just a few trials without a shock, 32% exhibited a slower rate of extinction, and 10% maintained their fear response after upwards of 20 trials.

“These are rats in a cage being shocked, not humans going about their lives being exposed to potentially traumatic stressors, but they’re showing the same kind of heterogeneity, and that really suggests that this is kind of an animal response — that this might be built in,” Bonanno said.

Diagnosis by Committee

The diagnostic criteria that designate what does and does not qualify as PTSD is itself somewhat arbitrary, Bonanno granted. Citing work by his former student, Isaac Galatzer-Levy (New York University), he noted that the diagnostic criteria for PTSD in DSM–5 allow for 636,120 possible combinations — a tremendous variability within the same disorder. This issue arises in part from the fact that the diagnostic criteria for PTSD are minimally scientific, Bonanno said. These categories are often determined by committee, where arguments and opinions can sometimes overpower empirical evidence.

The binary idea that an individual either does or does not have PTSD is also based on an artificially imposed cutoff line, Bonanno said. While conceptualization of PTSD as something you either do or do not have has led to significant advancements and interventions, it can also limit psychological science’s understanding of how individuals respond to trauma, he continued. “If two people don’t have a psychiatric disorder, it still doesn’t mean they’re equally healthy.”

Health is more than just the absence of disease, he continued. There’s a spectrum of responses within the “non-PTSD” category, and while some resilient individuals who have been through a traumatic event appear about as healthy as the average person, that doesn’t mean they’re completely symptom-free.

“We tend to think of symptoms as pieces of a disease; ‘you have symptoms of PTSD, so you’ve got a little PTSD.’ But that’s completely inaccurate because symptoms are just problems,” Bonanno explained. “Most of us have one or two symptoms [of psychopathology] at any given time. When we have a lot of them, then we start to have a bigger problem and we can start talking about mental disorders.”

Focusing on individuals who do not experience the years of elevated symptoms and distress that characterize chronic psychopathology can help researchers to better understand the full range of human responses to trauma, improving outcomes for everyone, Bonanno said.

The Roots of Resilience

Recruiting resilient individuals for these studies can be difficult; people who aren’t hurting often self-exclude because they assume that researchers only want to work with people who are traumatized.

This is part of what makes prospective studies, which recruit participants prior to potentially traumatizing events, so valuable, Bonanno said. Prospective studies also allow researchers to account for preexisting symptoms and to detect novel patterns that wouldn’t otherwise be visible.

In a prospective study of 205 caregivers responsible for their spouses prior to their deaths, for example, Bonanno and colleagues found evidence of preexisting depression in participants who responded to their loss with resilience as well as those who experienced symptoms of chronic grief, suggesting that depression itself was not the dividing line between these groups. Among these, there was also a subgroup of participants whose depression improved after their partner’s death — oftentimes, because they had been caregiving for a spouse they didn’t like, Bonano said.

Bonanno and Galatzer-Levy further examined the relationship between depression and trauma through a Psychological Science study of 2,147 adults before and after they experienced a heart attack. Leveraging existing data from the National Institute on Aging’s Health and Retirement Study, the researchers were able to track each participant’s symptoms of depression and levels of optimism over a period of 6 to 10 years beginning in 1994.

During that time, individuals who reported an increase in symptoms of depression after their heart attack were found to have a significantly higher mortality rate than individuals who did not experience an increase in these symptoms. Participants who were already experiencing depression before the heart attack but reported no increase in symptoms did not demonstrate this increase in mortality, however, and some even reported that their symptoms improved.

The study also linked optimism and resilience. Participants who had years earlier taken a brighter view of the future — that is, who reported believing they would live past 75 or leave an inheritance — were less likely to develop symptoms of depression in the wake of their heart attack, and they were thus less likely to die.

In a similar study of divorced individuals in Clinical Psychological Science, Bonanno, Galatzer-Levy, and Matteo Malgaroli found increased mortality only among participants who became depressed after their divorce.

“Becoming depressed after either a major health event or a major social stressor is increasing mortality; it takes its physical toll,” Bonanno said.

This appears to be true whether an individual experiences one or multiple potentially traumatic events, he noted. In a study of 1,395 individuals with lung disease, heart disease, stroke, or cancer, Bonanno and colleagues found that participants who became depressed after their illness demonstrated a similarly increased risk of mortality regardless of how many health events they experienced. In addition, participants who experienced more than one health event were just as likely to react with resilience.

“If people are going to be resilient, they’re going to be resilient if more than one bad event happens,” Bonanno said.

Optimism is just one of numerous factors that can contribute to an individual’s likelihood of remaining resilient in the face of trauma. Resilient individuals often possess greater regulatory flexibility, which helps them to develop and apply a more diverse range of coping strategies, Bonanno said. His lab is beginning to investigate the role of genetics as well.

Is there a gene for resilience itself? Not likely, Bonanno noted, but he and his colleagues are finding that individuals who are more resilient have less of a genetic risk for psychopathology.

References

Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2006). Psychological resilience after disaster: New York City in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attack. Psychological Science, 17(3), 181–186.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01682.x

Bonanno, G. A., Wortman, C. B., Lehman, D. R., Tweed, R. G., Haring, M., Sonnega, J., … Nesse, R. M. (2002). Resilience to loss and chronic grief: A prospective study from preloss to 18-months postloss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1150–1164.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1150

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bonanno, G. A. (2014). Optimism and death: Predicting the course and consequences of depression trajectories in response to heart attack. Psychological Science, 5(12), 2177–2188.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614551750

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Bonanno, G. A., Bush, D. E. A., & LeDoux, J. E. (2013). Heterogeneity in threat extinction learning: Substantive and methodological considerations for identifying individual difference in response to stress. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, Article 55. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00055

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bryant, R. A. (2013). 636,120 ways to have posttraumatic stress disorder. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 651–662.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613504115

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Huang, S. H., & Bonanno, G. A. (2018). Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 41–55.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.008

Malgaroli, M., Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bonanno, G. A. (2017). Heterogeneity in trajectories of depression in response to divorce is associated with differential risk for mortality. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(5), 843–850.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617705951

Morin, R. T., Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Maccallum, F., & Bonanno, G. A. (2017). Do multiple health events reduce resilience when compared with single events? Health Psychology, 36(8), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000481

Comments

I am most interested in this work. Before my retirement I worked in the field of child abuse. I became increasingly aware of the number of abuse victims who did not suffer the enduring consequences of abuse which others did. Significantly a proportion of these people felt they were the ‘abnormal’ ones. The concept of resiliency featured heavily in my reports for the British courts.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines.

Please login with your APS account to comment.